Part 1 - Canada

- Manning Depot, Quebec

- #4 Repair Depot, Scoudouc, N.B.

- #3 Initial Training School (I.T.S.)Victoriaville, Quebec

- Ancienne Lorette, Quebec

- #9 B&G Mont Joli, Quebec

- #1 Central Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba

- "Y" Depot, Halifax, N.S.

- Royal Air Force Ferry Command, Dorval, Quebec

- Back to "Y" Depot, Halifax, N.S.

Part II - Britain

-

Part III - Prisoner of War

Part IV - Home Stretch

Postscript

It seems strange to me now that I saw no signs of any farm people or Germans searching the area. I kept thinking about my folks and my friends back on the squadron and above all what happened to the rest of my crew. I don't recall being hungry however I did find some carrots that were growing nearby and chewed several Horlicks tablets that were in my escape kit. We had water purification tablets and I dissolved one in handfuls of canal water with no ill effects.

It was a long day lying in the tall grass and I was glad to leave my hiding place as soon as it grew dark. I had to cross two canals before reaching the dike and searched for fence rails or tree limbs that I could use. There were none around so I decided to wade, or if necessary swim across the narrow strip of water. I was wearing my Mae West so there was no danger of drowning. I ventured in and found the water only about two feet deep so I splashed across. I was glad to reach the firm footing and evan in my soggy socks it felt secure. I walked along in the darkness without any idea where I was heading. I didn't even know I was on an island — Rozenburg as it turned out to be.

There was no moon, however I could make out the outline of trees and bushes off to the side. The main problem was the lack of shoes and I had to pick my way carefully. After a time I could hear aircraft engines again and could see antiaircraft fire in the distance. It was the Rotterdam defenses blasting away at the squadrons of Bomber Command who were once again on their way to the Ruhr — this time to Gelsenkirchen which would claim two more crews of 427 Squadron including Francis Higgins who was my pilot when we had successfully crash landed in England after the Frankfurt raid in April.

There was no sign of civilization as I trudged along and after two hours or so, I was exhausted. I could make out some farm buildings and decided to rest and take my chances in the morning. I slept off and on and in the early dawn I could see that I was at the end of a lane leading to a farmhouse. Soon, a man came out of the house and headed down the lane in my direction probably to bring in the cows for milking. As he came opposite my hiding place, I stood up and it gave the farmer quite a start. I pointed to my uniform and explained that I was a British flyer. I spoke first in English and then in my best high school French. He didn't seem to understand, and then I pointed to the sky and held my arms in the air as if coming down by parachute. This he understood and beckoned me to come with him to the farmhouse. There seemed to be no one else around this early morning hour and the farmer produced a mug of milk and a chunk of cheese. It was the first real food I had tasted in nearly two days and then realized how hungry I was. A short while later, the outside door burst open and two Luftwaffe airman brandishing rifles appeared. For me the war was over.

I thought many times about my 'capture'. I don't know if the Dutch farmer by some manner or means called the Germans, or if someone else saw me enter the farmhouse. We had been briefed in Britain that if shot down over enemy territory, to seek help in the early morning hours when there were few people about. I tried this but it didn't work out. One Luftwaffe guards pointed to my stocking feet and asked the farmer for boots. He produced an old beat—up pair and I put them on. Off we marched down a narrow road leading to the coast. The young Germans spoke a little English and seemed friendly enough. We soon arrived at a small cluster of buildings which was an outpost of some sort. It may have been a wireless detachment although there were no massive aerials to be seen — and no sign of any antiaircraft guns. They ushered me inside and offered me a chair — I probably looked rather haggard at this stage. To my surprise they produced a great bowl of st rawberries and cream which I devoured. I don't remember much of what happened the rest of the morning. There were a few Germans about and one of them, a non-commissioned officer, I think, told me that I would be taken to the mainland. I could see the shoreline in the distance and knew then I was on an island.

In the afternoon, a German soldier arrived on a motorcycle equipped with a sidecar. He looked like a typical German wearing a stovepipe helmet and had a submachine gun. He motioned me to get in and I didn't argue. We roared away and headed down the road. In no time at all we arrived at the docks where a small ferry was moored. We drove on board and the ferry pulled out immediately as if it had been waiting for us. We disembarked on the Rotterdam side and my escort drove at quite a clip through the city. There was a large section that had been bombed and only partially cleared — devastation from 1940 when the Germans blasted Rotterdam after the Dutch had surrendered.

We soon arrived at a large military establishment which seemed to be an estate of some sort. By now it was early afternoon and there were lots of troops around, mostly Army. An officer who spoke some English, ushered me into a room and among other things told me that Max Shvemar was dead. I found this difficult to believe because Max had bailed out ahead of me apparently okay. I tried to ignore the information and the officer didn't have much else to say. I was given some soup, I think it was carrot or possibly turnip. He said to lie down if I wanted to. I felt okay but must have looked bushed with a great welt and swollen face. I remained on the base until around 5:00 p.m. when two Luftwaffe guards arrived to take me to the train station. We boarded an electric train and headed I knew not where. There were a few civilians in our railway car and no one paid any attention to me although my 'Canada' badges were in clear view on my battledress.

An hour later we arrived in another large city which turned out to be Amsterdam. At a suburban station we got off the train and the guards took away my boots presumably to return them to the Dutch farmer. It hardly seemed possible that it was only this morning that I had left the Dutch farmhouse. Here I am pattering along the cobblestone streets of Amsterdam in my stocking feet. A few hundred yards later we arrived at a large multi-story red brick building. It turned out to be a civilian jail taken over by the Germans to hold transient POWs. It was by now almost dark and as I was escorted upstairs I had some misgivings not knowing where I was heading.

I was led into a large room and was relieved to see a dozen or so guys in Air Force blue — mostly RAF and two airmen of the US Army Air Corps. I was on my guard because I thought there could be Germans planted in the group. One of the RAF officers was wearing the two and a half rings of the Squadron Leader and two gallantry ribbons, the DSO and DFM — an unusual combination. I thought he could be a German in disguise. How wrong I was. He turned out to be a legitimate RAF officer flying Stirlings on 7 Squadron, a Pathfinder outfit. His name was Colin Hughes and he became our Block Commander at Stalag Luft 3 a few weeks later. To show that it really is a small world, Colin lived about 20 miles north of Cobourg where I resided in the 1990s. He emigrated to Canada back in the fifties, worked in Toronto and later retired to rural Northumberland.

I found a bunk in the large common room and slept better than my two nights under the stars. Next morning we were herded out to a courtyard where there was a trough for watering horses. I was washing up when I heard my name being called "Whitey", the voice said. On looking up I spotted Jim Russell of 408 Squadron, whom I knew in the Mess at Leeming. He had been shot down on the Krefeld raid a few nights earlier. I totally ignored him as I thought any recognition would be a signal to the Germans that there was a connection. In the following weeks, and for the next 50 years, Jimmy Russell reminded me of the brush-off. He would say, " What were you thinking about? — for God sakes they knew more about us then we knew ourselves." As it turned out, Jim was absolutely right.

In our section of the jail there were guards on the door, otherwise we didn't see any Germans about. We were given black bread smeared with margarine three times a day and terrible tasting ersatz (artificial) coffee in the morning. At noon we were given a bowl of soup and that was it. We were told by the guards that in a few days we would be leaving for Germany. On the second day I was taken from the common room and marched down a long corridor. I was in stocking feet and in marked contrast the guard's jackboots made a racket on the cobblestone floor. We went down a flight of stairs and in the dim light I could see cell blocks — dungeons really. The guard wasn't rough but he prodded me into one of the cells and the door clanged shut. For the first time I felt like a prisoner and begin to worry. The one positive note was that a dozen or so Allied prisoners had seen me alive and could be witnesses to the fact in case I disappeared. No one came to the cell and I didn't have a clue what was going on. After what seemed to be three or four hours the same guard returned and, without so much as a word, marched me back to the common room and that was it. I have no idea to this day what the sojourn in the dungeon was all about.

Two days later it was announced that we were leaving for Germany and about 20 of us walked to the same suburban station where I had arrived a few days before. Some of those I remember were Colin Hughes, Max Ellis another Brit who will be mentioned later in this narrative, Cy Grant, a Negro (black) chap from British Guyana and who became part of my combine for the rest of the war. Jim Russell was also in the group and Major MacMillan a Texan and his navigator a guy named Forester from the same B—17 crew. By now I must have had boots but I don't remember where they came from.

At the station we were herded into a separate coach by the half dozen guards well removed from other passengers. I wish I had kept note since I have only a few recollections of our trip to Frankfurt which lasted two days. I remember in the early morning arriving in the Cologne railway station — the city had been heavily bombed two nights before. It didn't seem to be a great place to be with civilians peering in the windows. I'm sure we were recognized as POWs with guards standing at the doors. There was no ugly incidents here but outside Bonn the train stopped at a station and several burly guards appeared with several airmen in tow. They were a 35 Squadron Pathfinder crew shot down on the Cologne raid rate and the five or six survivors had been roughed up. One in particular had been badly beaten. His name was Tony Sachs, an air gunner wearing the DFM. The Germans were incensed that a British airman with a German name would have the audacity to bomb the cathedral city of Cologne, or any other city for that matter. All of the crew had bailed out except the Canadian pilot 'Ty' Cobb DFC who went down with the Halifax. I got to know this crew very well in the weeks to come, especially the WAG, Charles 'Doc' Bulloch DFM from Lachine, Quebec and we remain close friends to this day. The navigator in the crew was a Brit named David Codd DFC whom I still see at reunions.

We crossed over to the east side of the Rhine and followed this famous water passage for most of the day. We saw several ancient castles built high on the cliffs overlooking the river. It felt like we were on a holiday until we looked at the glum guards at each end of the car. Also the black bread for lunch was not standard dining fare on CN or CP trains back home. In the afternoon we swung east and I remember passing a huge factory with OPAL printed in large letters on one of the chimneys. Being a pre-war auto plant, it would have been a wonderful industrial target for our bombers since I'm sure they were manufacturing trucks or tanks for the military at this stage of the war.

In late afternoon in a station west of Frankfurt I remember seeing a hospital train on one of the other tracks. Each car was jammed with stretchers floor to ceiling with the wounded troops being swathed in bandages clearly visible. One of the guards muttered," Ost front", which translated means East front. These unfortunate soldiers had taken a pasting at the hands of the Red Army. In a way I felt sorry for them although they, like ourselves, were perhaps the lucky ones.

We arrived in Frankfurt in the early morning and I can't remember now whether we detrained in Frankfurt or were taken to a suburban station. Our destination was on the outskirts at a place called Oberursel sometimes shown in books as Oberwesel. At any rate we walked to the camp which bore the name Dulag Luft. It was a transient interrogation centre operated by the Luftwaffe for Air Force POWs. We were taken to a cluster of huts somewhat removed from the main camp. I was put in a room with the US Army Air Corps officer from Cleveland with the German — American name Meyer. I had seen him on the train so figured he was a real POW and not a plant. We had the same food as before, black bread and soup. The next day we were allowed out for a breath of fresh air and I spotted Jimmy Russell looking sad and forlorn. I learned the reason as he hauled out a few photos from his battledress pocket. They were pictures of his wife Mary, a real beauty. They had married just before Jim headed overseas in this very day was their first wedding anniversary. James Coyle Brown Russell was not a happy camper.

Later we were moved to the main camp and were placed in solitary. I was thankful it wasn't anything like the Amsterdam dungeon. My cell was a small room with a barred window near the ceiling. I couldn't see out even by standing on the cot but at least a shaft of daylight found its way in. I had nothing to read and no writing materials. In a short time it becomes very lonely and boring and it was a welcome relief when the guard would come to take you to the washroom or bring bread and soup. We soon learned that the German word 'essen' meant to eat. At first we thought the guard was probing for target information and was referring to the industrial city of Essen as he shouted the word "essen" through the door. All that he was doing was announcing the arrival of food.

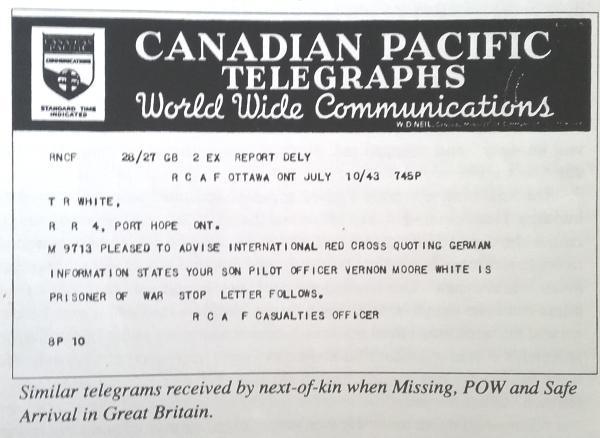

The following morning there was a knock on my door and a distinguished white-haired gentleman in a tweed sport jacket appeared. In perfect English he announced he was from the Red Cross and I had a form to fill in so that my next-of-kin could be notified that I was safe. I took the form and could see that it was an official looking document. The first three lines were Name, Rank and Serial Number which I filled in. The rest of the form were questions relating to my squadron number, my home base, the names of the crew, details about our bomb load and much more. I realized then that the visitor was phony and we had been warned on the squadron that this was common practice by German Intelligence. I handed the form back with only the first three lines completed. At first he tried to be persuasive by saying,"You want your relatives to know you are safe don't you, otherwise they have no way of knowing." I explained that under the Geneva Convention I am only required to provide the information already given. The conversation continued in the same vein for several minutes and I still steadfastly refused. The phony Red Cross rep then showed his true colours and with a red face said, " You will be sorry" and stomped out. Nothing else occurred for the rest of the day.

The following afternoon a guard appeared and took me over to another building. I was ushered into an office an the guard left, probably remaining outside the closed door. Seated at a desk was a Luftwaffe officer who motioned me to sit down. In perfect Oxford English his first words were, " Too bad about F/L Webster". This startled me because Webster was one of the four pilots from our squadron shot down on the Mulheim raid two nights before we met the same fate. I tried not to show any reaction but as the interrogation proceeded it was apparent that these guys were very good at their job. He went on to say, "You wouldn't fill in the form but we know all about you." He then recited our squadron number, where we were based, the aircraft we were flying and much more. He was wrong on a few minor points but it was obvious they had a very complete file on 427 Squadron and the Leeming RAF base. At one stage the interrogator expressed wonderment that Canadians would be involved in a war that had nothing to do with Canada. I explained that we are members of the British Commonwealth and very loyal and totally committed to the cause. He asked about electronic equipment we were carrying. I don't know what he was fishing for since he already knew the aircraft we were flying. In retrospect I have wondered if he was trying to find out if the regular squadrons were being equipped with H2S or some of the other sophisticated gear that the Pathfinder squadrons had at this stage (later in the war all the heavy bomber squadrons were so equipped). He kept coming back to the subject of electronic equipment and I reminded him that it was not my department. The interrogation lasted perhaps an hour after which the guard took me back to my cell.

Later that same evening I was escorted from the holding block and taken outside. As we walked across an open area I can still remember the smell of the sweet summer air. I hadn't realized how stuffy my small room had become. I entered a barrack block where there were a number of Air Force prisoners. One of them was resting on a lower bunk and as he sat up I noticed he was missing a leg. He introduced himself as Don Morrison. I recognized the name immediately as a well-known Canadian fighter ace. He had gone missing the previous autumn and only now had reached this transient prison camp. He had been in various hospitals all this time recovering from his terrible wounds. In the interests of security, I felt that I had still had to be careful who I talked to. In Don Morrison's case there was no doubt that he was legit since his picture had appeared in the RCAF newspaper Wings Abroad several times. He was a likable guy then, and didn't change in the next 50 years that I knew him. He had no artificial limb and cheerfully hobbled about on crutches.

I was given a meal prepared by POW kitchen staff using ingredients from Red Cross parcels. It was my first introduction to Red Cross food which was to be our salvation for most of my time as a POW. I was beginning to realize how fortunate I was as I begin to meet the remnants of other crews shot down in recent weeks. On my second day out of solitary I was delighted to spot a familiar face — it was none other than Larry Bone my wireless operator. He was just leaving for one of the permanent NCO Camps and we had only about five minutes to talk. He didn't know anything about the rest of the crew since he was captured the first morning. I told him that the Germans in Rotterdam had reported that Max Shvemar,our navigator, was dead and Larry was surprised since he too knew that Max had bailed out apparently okay. We said a hurried goodbye and that was the last time I saw Larry Bone although we corresponded after the war. We lost touch when Larry did not respond to several of my letters. About ten years ago I learned that he emigrated from Burnley, Lancashire to Australia in 1963. We resumed correspondence and Larry contributed to Roy Nesbit's book Failed To Return (as I did), Larry passed away in 1996

Top | Back | Next

To continue select Back or Next which will move you consecutively, back or forward, through the book or make a selection from the column on the right which will take you to that part of the book.