Part 1 - Canada

- Manning Depot, Quebec

- #4 Repair Depot, Scoudouc, N.B.

- #3 Initial Training School (I.T.S.)Victoriaville, Quebec

- Ancienne Lorette, Quebec

- #9 B&G Mont Joli, Quebec

- #1 Central Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba

- "Y" Depot, Halifax, N.S.

- Royal Air Force Ferry Command, Dorval, Quebec

- RAF Repat Depot, Moncton,N.B.

Part II - Britain

-

Part III - Prisoner of War

Part IV - Home Stretch

Postscript

During the next few days we picked up two additional members – Jim Lynch of Peterborough, Ontario (mid-upper gunner) and William "Jock" Arthur of Ayrshire, Scotland (flight engineer). A crew of seven was needed to man the flight positions in a Halifax. Half the squadron began their conversion training right away and moved temporarily to 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit at Topcliffe a few miles away. The rest of us including our crew were sent on leave which was a pleasant surprise. Max and I headed for London and booked in to the Strand Palace which seemed to be a favourite hangout for Canadfian aircrew.

I stayed in London for a few days and among other things attended church service at St. Martins-in-the-Fields. I mention this only because Max, who was Jewish, accompanied me. He said he sometimes attended a United Church in Montreal with friends and we managed to stumble through the Anglican service. My pay records were still fouled up dating back to the announcement of my commission three months before. I hadn't yet received a dime, or even a schilling, as an officer. I had no other choice than to go to RCAF Pay & Accounts branch in Knightsbridge and withdraw more funds from my deferred account in order to keep body and soul together. I left for Edinburgh and spent the rest of my seven day leave at the same Club as on my previou visit. I saw my little Wren friend - as nice as ever but still smoked like a chimmney.

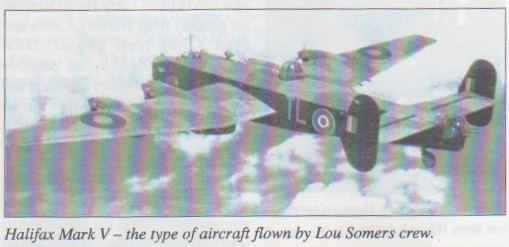

On returning to Leeming we received news that 427 (Lion) Squadron was to be adopted by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the movie studio. This honour was entirely through the eforts of our Adjutant Jay Chasanoff who had connections everywhere and extraordinary persuasive powers. We learned that each Halifax aircraft would be named after a Hollywood movie star and the pilots would draw names. The number one choice was Lana Turner, a blonde beauty with a gorgeous figure to match. Other favourites were Hedy Lamarr and Greer Garson. To show that even in those days there was equal opportunity, other stars that I recall were Abbott & Costello, Judy Garland and Robert Donat. We were told that a special adoption ceremony would take place at Leeming in a week or so. In the meantime we moved over to Topcliffe and commenced our conversion training.

While Lou Somers was learning to fly a four engine bomber, the rest of the crew went to ground school polishing up our trades. The feature item for the bomb aimers was introduction to the Mark XIV It was reputed to be far superior to the old Mark IX since many of the previous manual settings are made automatically on the new model. For instance, the airspeed and altitude instruments were connected electronically to the bombsight and the settings changed automatically according to the height and speed up the aircraft. Similarly the bombsight was controlled by a gyro compass which allowed for banking and turning of the aircraft. All this had the potential for greater accuracy with the elimination of many of the variables. Whether we could drop a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet as the Americans claimed with their Norden bombsight remained to be seen. We knew that we still had the wind to contend with.

At Conversion Unit we sometimes shared an aircraft with Bill "Indian" Schmitt's crew and occasionally flew together on local training exercises. The Indian had already wired a reputation of being an excellent, fearless pilot but a wild and woolly character with a crew to match. More than once the squadron brass had to go to town to get some of the crew released from jail for some caper. The one exception was the bomb aimer Lindsay "Lefty" Vogan, who was just the opposite. Like myself he was trained as an air observer and fully qualified in navigation. Lefty was a very religious type and said that he would pray while over the target when Indian would fly straight and level longer than necessary in order to obtain a good photograph. We gained great respect for Indian's ability as a pilot as he put the Hally through its paces on some of our training exercises around Yorkshire. As a footnote, Indian Schmitt's crew was the first to complete an

operational tour on our squadron. They all survived the war and settled down in civilian life. Oh yes, Lefty Vogan became an ordained United Church minister – apparently all that praying paid off.

Part way through our training, the MGM adoption ceremony took place as scheduled and all aircrew converting at Topcliffe went over to Leeming by lorry. The ground crew were already there and we joined them in a hollow square with a Halifax aircraft in the background. It was a spanking new Mark V which was the latest model in May 1943. On the nose was a colourful work of art showing a winged lion clutching a high explosive bomb and the caption "London's Revenge". This was to be Lana Turner's aircraft to be chosen by lot by the pilots.

There were speeches by Wing Commander Dudley Burnside and by Mr. Sam Eckman Jr., head of MGM in Britain. Also present was senior officers, including Air Marshal Slemon from RCAF HQ's (Overseas). Mr. Eckman announced that, in due course, a medallion would be presented to each squadron member giving the holder the freedom of MGM theatres, presumably for life. Medallions didn't arrive during my time but other members including ground crews eventually received theirs and put them to good use. There are very few medallions in existence today and of no practical value since Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has undergone several corporate restructurings and is no longer a movie producer.

Getting back to the adoption ceremony, Mr. Eckman presented a handsome, sculpted, bronze lion to Dudley Burnside as a memento of the occasion. The lion remained at Leeming until the end of the war and it then disappeared for 30 years. I won't go into details but it turned up in England in the early 1970s, was returned to 427 squadron at Petawawa and occupies a prominent place at Dress Parades and official squadron functions.

The lottery to select Lana Turner was the next item of business and the winner was Sgt. Eric Johnson RAF. There was a great round of applause as Johnny or Limey, as he was also called, proceeded to print Lana Turner's name in block letters across the nose of the Hally. Sam Eckman then did his thing by printing on one of the 500 pounders in the open bomb bay, the inscription - "To Adolph with Love from MGM". There was a party in the Mess afterwards and then we returned to Topcliffe to continue our conversion training. I've been asked the name of our movie star and that I can't answer. At the time of the draw there were more crews than aircraft and we didn't have one of our own.

Back at Topcliffe we lost no time in completing our training. We flew four cross country flights in the space of five days, one of them at night. We also spent several hours on local flying, part of which was in-flight training on the Mark XIV bombsight. On this exercise I had as my instructor a smashing looking young gal. She was a civilian clad in airforce blue battle dress and she crawled out into the nose of the Halifax with the bomb aimers checking and explaining the settings - we were all slow learners. Unfortunately later in the war, this young lady met an untimely end. On a training flight in another squadron, the aircraft crashed killing all on board.

Villagers came down to see us off. At this stage we didn't know any of them - they just wanted to.

Some of the 427 crews started their training ahead of us and were now returning to operations at Leeming. The first target was Wuppertal in the Ruhr and we at Topcliffe were glad to hear that all crews made it back to England, however two aircraft were badly shot up and one of them crash landed at a base in the south. I mention this because the bomb aimer, Jerry Millard suffered a broken back and was hospitalized for many months. His navigator was Jim Dobie. What a

coincidence. Both guys had been my flying partners at navigation school - Jerry at Ancienne Lorette and Jim at Rivers. Both had graduated as Observers. At Bournemouth, one chose the navigator route and the other chose bomb aimer. They met at OTU and immediately decided to crew up together. This was not uncommon at this stage of the war, and on our squadron alone we had six former Air Observers who ended up as the NAV/BA team on three crews. I had been with all

but one of them on Ferry Command and were good friends. Regrettably four of the number were killed that summer and Jim Dobie was taken POW on the famous Peenemunde raid. The sixth member, Jerry Millard recovered from his broken back and flew a tour on Liberators in Italy on an RAF Squadron. Another coincidence - his navigator was my former chief instructor at Rivers, J.E. Riddell who had certified my log book when I graduated.

Our crew returned to Leeming early in June and flew our first Halifax operation to Dusseldorf on the night of June 11. The briefing was handled by one of the Flight Commanders, Bill McKay of Vancouver, and so we were off to the Ruhr once again but this time as a 7 man crew in a four engine bomber. Our dispersal site was on the west side of the drome near a road and a few

bid us bon voyage. It was quite a sight and sound for them as more than 30 aircraft from the two squadrons fired up their engines all around the airfield and one by one lumbered out onto the perimeter track that would take them out to the take off point. As they had done at Croft, the ground crew and other base personnel gathered near the departure point and gave each Halifax a thumbs up as we hurtled down the runway a few minutes before midnight (double Daylight Saving

Time).

As usual on a trip to the Ruhr, we crossed the English Coast at Flamborough Head and headed out to sea. The only difference this time was the sound of the eight Brownings being tested as both gunners got off a few short bursts. It was somewhat reassuring to know that we now had a second air gunner and an extra pair of eyes. This trip was quite uneventful and I won't go into details. It was one of the few times that I could pick out the Rhine River in the industrial haze. Lou let me fly the Hally for about an hour on the way home after we got well clear of the Dutch coast. I had been doing this on some of our training flights around England. Flying straight and level was no big deal and I had no difficulty altering course or changing altitude. It gave me a certain amount of confidence but I wasn't kidding anybody. The stuff I was doing was the easy part. We landed and were debriefed, quite pleased that we completed our first operation in a four engine bomber. It was broad daylight when we hit the sack.

Around noon we were roused with the news that we were on ops again that night. It seemed we had only turned in. It was not uncommon for us to fly on consecutive nights when the weather was favourable - it just hadn't happened to me thus far. We made a visual inspection of the aircraft, all the while wondering where Air Marshall Bomber Harris would be sending us tonight. It turned out to be Bochum in the Ruhr, which I, unlike the rest of the crew had visited before. We were assigned to be in one of the early waves which meant that the raid would be just nicely underway by the time we arrived. This was to be our undoing or nearly so.

The trip across the North Sea was routine and on this night we crossed the Zuider Zee north of Amsterdam with a flight plan that would approach the Ruhr from the north. All seemed to be going well and Max calculated that we were five minutes from the target. Usually the target was well illuminated by the time of arrival - all that we saw were a few searchlights and moderate flak on our port beam - there was no sign of the Pathfinders markers that we could see. Just then searchlights lit up the whole sky with flak bursting all around us. We realize that we had wandered slightly off course and were over Essen, the hotspot. To tell what happened I will quote from excerpts of the story filed by the (Toronto) Telegram war correspondent Major Bert Wemp in the issue dated June 18, 1943. Bert Wemp happened to be at Leeming when we landed and interviewed our crew with the okay of the squadron debriefing officer.

Quote from Lou Somers:

Our navigation had gone wrong and we started to stooge toward Bochum, but just as we turned, the Essen guns opened up with everything they had. They coned us eight times with at least 100 searchlights. I sure weaved that kite all over the sky. Our bomber aimer Flying Officer V. M. White, Port Hope said that there must have been 50 ack ack barking at us with heavy predicted flak. The Halifax was holed 20 times, both inboard engines were hit but luckily didn't conk, while the starboard rudder, fuselage and main plane also took a severe beating. Our rear gunner, an English lad did a swell job of giving me evasive action and at one time we dived from 19,000 to 13,000 feet. We finally got clear of the flak and searchlights and flew North. " The article goes on to say " the crew never became panicky but went about their job in a business-like way, but at times when the flak was like hail we thought we'd had it ."

We made our way to the coast without further incident and started the sea crossing with some apprehension. Carefully nursing the engines, we made it back to Leeming well past our ETA. The rudder controls were severely damaged but Lou bounced the Hally to a good landing - by definition a good landing is one you can walk away from. The Telegraph article referred to above bore the headline

Toronto Flyer Takes Plane alone through Essen Barrage

It was on the same Bochum raid that the squadron lost its first Halifax. Lou Fellner and his crew is missing. They were the very first crew posted to 427 Squadron at Croft, known to

all as well liked. We didn't know it at the time but other losses would quickly follow I'll have more to say about the Fellner crew later in this narrative.

We were now beginning to feel at home at Leeming and learned to appreciate the comforts of this pre-war RAF base. No operations were scheduled for the next few days but since the Halifax was still new to us it was a time to brush up on fundamentals. In addition to one or two local training flights, we practised dinghy drill, parachute drill (we didn't actually bale out) and what to do in the event of a crash landing. There were specific duties for each crew member to perform in case of an emergency and a prescribed sequence for leaving the aircraft. We had to practice some of this at Conversion Unit but little did we know that we would soon need this refresher training.

In the first few weeks the aircrews and the ground crews got to know the local watering holes in Bedale and other nearby villages. Being the epitome of sobriety, I didn't imbibe and neither did my navigator Max Schvemar or Stu Dunbar my roommate. We learned of a place in Ripon, near the famous Cathedral, where the proprietress served steak, eggs and fresh green peas. An unlikely combination perhaps but a super meal nonetheless and a break from kippers and brussels sprouts served in the Mess. We also went to Harrogate an attractive town with lovely gardens and fine public buildings. One such place was the Baths - it might have had a more elaborate name which I've forgotten. It had an indoor swimming pool, a dance hall and an auditorium for concerts. There were dances on Saturday nights where I met a young lady whose surname happened to be White - first name Margaret, I think. She was in the Woman's Land Army which meant she worked on a farm as part of the war effort. Many of the Land Army girls were from London and other large cities doing their bit to help feed the nation. Their uniform if one can call it that, was a khaki blouse, a green pullover sweater and khaki corduroy breeches. A practical outfit for working in the fields or cleaning the stables but not party garb by any stretch imagination.

Our next operation was on June 19. The target was a large automotive plant at Le Creusot about 170 mies southeast of Paris.From the north of England we flew down the full length of the country keeping a watchful eye for other aircraft as they joined the bomber stream. It was a moonless night but otherwise clear and we were able to get an accurate pinpoint as we passed over the English coastline. We didn't know it at the time but we crossed over the French coast where the D-Day landings would take place a year later. To avoid the light ack ack fire , we were ordered to cross the French coast at 10,000 feet and then drop down to 5,000 feet before reaching the target. To help us stay on track, the Pathfinders dropped aerial flares at the turning points between Normandy and the target. Over Germany this would have been suicide but it was felt to be worth the risk in French skies where there few fighters about. No markers were dropped at the target, just aerial flares and we were required to identify the factory buildings visuallly.Our bomb load consisted of high explosives only , no incendiaries were dropped to minimize the damage to the town itself.

Our return flight was uneventful — we already knew we would have to refuel and were directed to Tangmere, a famous Battle of Britain fighter station. It seems that half of 6 Group were there getting gassed up or should I say — petrolled up. We had been in the air well over seven hours and an hour later headed back to Yorkshire. It had been an easy operation

and of the 300 aircraft involved only three were lost — one of which was from 408 squadron, our sister unit at Leeming. Our squadron did not escape unscathed however as the Wingco caught a packet of flak crossing the French coast on his way home. One of his gunners Rocky Durocher, the Gunnery Leader was wounded in the foot and hospitalized for a time. Rocky return

to operations some months later and completed his tour with W/C Bob Turnbull who succceded Dudley Burnside as C.0. Rocky is a retired Engineer, resides in a Montreal suburb and we often met at reunions until he passed away in 1999.

Our next stop two nights later was the only time we ever turned back before reaching the target. Early returns were a problem especially with less experienced squadrons and the aircraft captain had to have an awfully good reason to justify returning to base. The target was Krefeld in the Ruhr and should have been a straightforward operation. Our mid-upper gunner Jim Lynch of Peterborough took ill and Dave Ross the Wingco's gunner volunteered to fill in. We were delighted. Davey was the most experienced air gunner on the squadron, holder of the DFC and already halfway through his second tour. It was like having an insurance policy.

Our flight plan was similar to others to the Ruhr and we crossed Flamborough Head dead on track. It was only when we reached an altitude of 10,000 feet halfway across the North Sea that we realized we had a technical problem. It wasn't the engines overheating or the instruments malfunctioning but something as mundane as a faulty oxygen supply to the mid-upper gun position. It had been tested on the ground but now that we were airborne, Davey found that he had no oxygen. The flight engineer checked it out — couldn't find the problem — the gremlins had done their work. Davey who was a very keen type suggested we fly to the Ruhr at 10,000 feet or so and he would be okay. Lou said not a chance. Davey then suggested that he make do using the portable oxygen bottles we carried. Again Lou wouldn't hear of it. We wouldn't get to the Ruhr before the emergency supply was exhausted, much less get home. As captain, Lou made the decision not to expose a valuable four engine bomber and a seven man crew to this kind of risk and reluctantly made a wide 180 degree turn and set course for Yorkshire. We couldn't or wouldn't land with a full bomb load and I jettisoned the lot safe over the North Sea. A waste for sure but standard procedure in such circumstances. The early return was a huge disappointment to the crew since it would have been one more operation under our belt. This one didn't count toward the standard tour of 30 and there was nothing we could do to change that fact. Losses were heavy on the Krefeld raid — 41 aircraft of which three were 408 Squadron Halifaxes. One of the missing navigators was Jim Russell, Canadian, who I knew in the Mess at Leeming. We found that he had been at Rivers at the same time but our paths hadn't crossed. I would meet James Coyle Brown Russell again sooner than I expected

It was back on ops the next night (June 22) again the Ruhr — the target was Mulheim. We contributed 16 Halifaxes, a record number for the squadron at this stage of the war. Once more we were flying with a spare mid-upper gunner — I don't even know his name. The Mulheim operation went like clockwork. The Pathfinders did a great job as they positioned their ground markers perfectly in concentrated clusters. We were dead on time and weaved our way to the target through the heaviest flak I had ever seen (and that includes Essen and Frankfurt). As we were bombing, a burst of flak got us below the nose and a shard pierced the perspex about 18 inches from my face. I could feel the cold air ventilating the front section. There were other hits on the aircraft but miraculously no one got a scratch. Lou flew the aircraft straight and level long enough to get a good photograph and wheeled away from the target area which by now was a mass of flames. We completed the trip home without incident, and when well out over the North Sea, Lou let me fly the aircraft for about an hour. What I was doing was pretty straightforward but good practice nevertheless. Even with a substitute gunner we were beginning to fit together as a crew.

At the briefing we learn that four crews were missing and initially this was no cause for alarm. They could be flying at reduced speed due to battle damage or mechanical failure or more likely have landed at an emergency drome on the coast. By the time we had finished breakfast there was still no word from any of the crews and we all started to worry. Up till now our losses had been minimal, one or two planes at the most. We had no choice but to get some sleep and has we turned in we hoped there would be better news. I wakened in mid-afternoon and with my roommate Stu Dunbar hurried over to the Mess where a glum group of lions confirmed the worst — no word from Webster, Cadmus, Hamilton or Reid. They were competent crews and all listed as missing. We knew that operational flying was a deadly business. The only crew with less than five trips was the one captained by Reid. He had been an instructor in Canada and the holder of the Air Force Cross. He was an excellent pilot and keen as mustard. There was a touch of irony and sadness surrounding Reid's crew. Only the day before, A Canadian Army Sergeant came to visit his brother F/O Bryon Gracie. They had a short visit and planned to spend a few days together. This was not to be since the young wireless air gunner was a member of Reid's crew and his brother waited around all day hoping for good news that never came. In my post-war trips to Holland and in reviewing casualty lists, I learned that the Cadmus crew was shot down on the German — Dutch border and the other three over Holland itself.

of the 28 missing airman there were only two survivors.

There was no flying the next night but it was only a short breather. On the night of June 24 we were briefed for Wuppertal in the Ruhr. Happy Valley, as it was called, was getting hammered regularly on the short summer nights. Due to the heavy losses on Mulheim our squadron had fewer aircraft available and there were a lot of empty seats in the briefing room. Jim Lynch our mid-upper gunner was still ill and his replacement was a chap named Walton from and be Nova Scotia. He was older than the rest of.

After briefing I went to the mess and before our flying supper I recall chatting with Red Soeder with whom I had flown in Ganderton's crew to Bochum in March. We talked about the loss of our four crews on Mulheim and I vividly remember Red saying that there was a 50 — 50 chance of survival in Bomber Command. He meant it as a positive statement. In this case he was correct his mathematics. Red was killed on the notorious Nuremburg raid in March 1944 and I would survive the war. After what turned out to be 'The Last Supper', I played shove ha'penny with the R.C. Padre. This was a board game, the object being to shove a penny from one end to the other, closer to the back edge than the opponent without going over.

We went down to the hangar about an hour before dusk to don our flying gear. As usual there was transport waiting and another crew clambered in with our gang. The WAAF driver delivered the crews to their respective dispersal sites scattered around the drone. We made last-minute inspections inside and out and the smokers had a last drag on a cigarette. Everything checked out OK and after running up the engines, Lou taxied out to the perimeter track and began the circuitous route around to the take—off point.

In order to recount the details of the rest of the flight, I will now quote liberally from the book titled Failed To Return by Roy Nisbet who chronicaled our last flight as part of his narrative concerning the work of Gerrie Zwanenburg, a Dutch specialist in aircraft recovery. Upon request I gave the details to Nisbet which he incorporated into his book.

They (meaning our crew) crossed the English coast dead on track, and then experienced the familiar feeling of loneliness as they headed over the North Sea. When they were well clear of the coast, Walton tested his guns in the mid-upper terret and Ashby did the same in the rear turret, with an extra burst for good measure. About an hour later, they could see flak burst ahead, coming from the Dutch coast. The flak was not intense, but showed that the Germans were ready. Shvemar asked Bone to check their position using the bearings from two ground stations. At this stage of the war the Germans were jamming the navigator's Gee radar sets. Then he told Somers that they seemed to be slightly ahead of their position, with a stronger tailwind than forecast. The aircraft was also slightly to starboard of their intended track and a little alteration of course was required. Shvemer suggested to Somers that he throttle back a little to regain their correct position in the middle of the bomber stream. Then he asked White and Ashby to try and pinpoint position visually as they crossed the enemy coast.

The Halifax was at 18,000 feet and the night was bright stars. It never seemed to get completely dark at that height in the mid summer sky. Looking up, White see another aircraft about 500 feet above them, it appeared to be a Wellington and was flying in the same direction. Moments later, as they were crossing the coast line, there was a tremendous jolt and a series of dull sounding explosions felt throughout the aircraft. The port engines were immediately put out of action and the pilots instruments begin to spin madly.

There was no panic in the stricken Halifax, although the crew did not know whether they had been hit by flak or canon from a night fighter. Arthur peered over Somers' shoulder, watching the instrument dials while the pilot activated the fire extinguishers, feathered the propellers in the two port engines, and tried to bring the aircraft under control with the two starboard engines. Standing beside Somers, White could see that they were losing height.

" Get rid of the bombs" Somers said to White. The bomb aimer went down into the nose and press the jettison switch. He could see from the indicators that the containers of 4 pound incendiaries fell away from the wings but all the stations in the bomb bay, consisting of the 1000 pounds bombs and 30 pound incendiaries, remained in position. It was evident that the release mechanism had been shot away. White scrambled back to the pilot and began to ask Arthur to remove the plates in the floor of the fuselage and to try to pry the bombs loose. Meanwhile the fire in the port wing had gone out, and the Halifax was in a downward spiral.

As White was speaking to the flight engineer there was a violent thump underneath the aircraft and entire fuselage from the mainspar backwards burst into flames. The crew thought that the aircraft had been hit again, but this was probably because by an explosion in the fuel tanks.

" Bail out! Bail out!" Somers called urgently over the intercom. White handed Somers his parachute back and clicked his own pack on his parachute harness. He then went forward to the escape hatch beneath the navigator's compartment. Shvemar was having difficulty loosening the hatch but the two men wrenched at it until it came free. The navigator was such a big man that, encumbered by his Mae West life jacket and parachute pack, he was barely able to squeeze through and White helped by pushing him. The bomb aimer followed immediately.

Behind Somers, Bone pressed the 'destruct' button of his IFF set, clipped on his parachute pack, went forward to the same exit. He paused as he passed Somers and called, "Are you all right?". The pilot replied with a thumbs-up sign and motioned towards the emergency exit. The wireless operator continued forward to find the hatch already open. He sat on the edge and roled forward without difficulty into space.

The slipstream tugged at Vern White's flying boots as he left the Halifax and tore them off, leaving him with three pairs of woollen socks on his feet. At about 13,000 feet, he pulled the ripcord of his chest pack and took a stunning blow on his face as the pack whipped upwards, knocking him unconscious. But the canopy opened and he was still floating downward he came to, in the darkness and stillness apart from some flares he could see to the east.

Now when floating down over Holland, Vern White's thoughts were of his parents and his home in Canada. Then he remembered, perhaps incongruously, that he had a date with a Land Army girl the following Saturday. He thought she would be annoyed in the belief that she been 'stood up' by an unreliable Canadian. But these thoughts went out of his mind as he neared the ground, for he could see that he was over the sea, with the gentle breakers leaving lines of florescent whight along the shoreline. He pulled on the shroud lines and, either by good management or the help of a favourable wind, drifted over land. There was no further injury on landing, although he could feel a painful welt on the side of his face. Several Holstein cows wandered over to inspect the intruder who had landed in their field.

Thus I had arrived in Holland and this concludes Part II of Four Years and a Bit. Part III would deal with my time on the continent and eventual return to England.

Top | Back | Next

To continue select Back or Next which will move you consecutively, back or forward, through the book or make a selection from the column on the right which will take you to that part of the book.