Part 1 - Canada

- Manning Depot, Quebec

- #4 Repair Depot, Scoudouc, N.B.

- #3 Initial Training School (I.T.S.)Victoriaville, Quebec

- Ancienne Lorette, Quebec

- #9 B&G Mont Joli, Quebec

- #1 Central Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba

- "Y" Depot, Halifax, N.S.

- Royal Air Force Ferry Command, Dorval, Quebec

- RAF Repat Depot, Moncton,N.B.

Part II - Britain

-

Part III - Prisoner of War

Part IV - Home Stretch

Postscript

For me it was easy. In our barracks there was a 19-year-old pilot from Toronto whose name was Andrew McFarlane Harrison

'Drew' Gain. He had a terrific sense of humor and could do wonderful impersonations of Winston Churchill. Drew was a likable sort

and when he asked me if I would consider being a member of his crew I was delighted. Drew said he was glad to have me because

of my navigation training which to him was a bonus. Within the next few days we met others in the sergeants mess and settled on

three Brits who seemed like good types. The navigator was Eric Antrobus, age 19 from Lancashire; Rex Caplin, age 21 from

Harwich; Don Burge, age 18 from suburban London. I was 20 years of age which made us a very young crew to be operating one

of his Majesty's expensive aircraft in the skies of Europe. We fitted in well together and it showed that the somewhat unscientific

method of crew selection usually worked.

Our pilot, Drew, was learning to master the Wellington bomber and this required several weeks of instruction and practice before we

flew together as a group. The rest of us had specialty training in our respective fields. The first time I was airborne in a Wellington

was on November 23, 1942. I was one of several Bomb Aimers and Gunners who flew to Cardigan Bay on the Welsh coast for

practice in air to sea firing. It was our first experience firing twin Brownings, from a power-operated gun turret, quite different from

the single Vickers at Bombing and Gunnery school. We all got in a lick or two and it was fun as we sprayed the Irish sea with the

stream of bullets.

On the return trip over the Welsh hills the weather closed in and we couldn't see a thing. So much of the time the weather was

absolutely beastly and was a major factor in many of the prangs (crashes) in wartime Britain. We couldn't find Pershore in the murky

skies and the pilot, who was an experienced instructor, found an opening and let down at the first airfield he could find. It turned out

to be Gaydon which was a satellite base for another OTU in the Midlands. We stayed overnight since it was impossible to take off.

In the Sergeant's Mess I was pleasantly surprised to see Stan Gaunt who was training there. I had been with Stan at Manning Depot,

Guard Duty and I. T. S. I hadn't seen him in a year and we surely got caught up on the news. Stan hailed from Rhode Island and

was a good friend of John Godfrey mentioned earlier. A number of the Americans had already transferred to the US Army Air Corps

after graduation. Stan was still a Sgt. in the RCAF at Gaydon. He later posted to squadron in 6 Group and was awarded the coveted

Distinguished Flying Medal early in his tour. When I last heard of him he was a Second Lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps and

was continuing to fly with his Canadian squadron.

By now I had been at Pershore for several weeks and I must say I wasn't enjoying the place very much. It was cold, wet and foggy

and our only source of warmth was the small stove in our hut that seemed to give off more smoke than heat. The Sergeant's Mess

had a sort of lounge where we could read magazines and hear some of the NHL hockey games - they were pre-recorded. Best of all

I was getting letters from home again and several parcels came all at once from friends and relatives. I remember in one of them was

some maple sugar and I shared it with the English guys in my crew. I told them it came out of trees and one of them in disbelief said,

"Oh you Canadians are always joshing." In another parcel was a box of chocolates from Dr. McDerment who was our family

doctor in Port Hope. The parcel must have been salvaged from a torpedoed ship or something. The chocolates look great but

tasted like kerosene. I asked mother to thank the good doctor but not to mention the petroleum flavor. His thoughtfulness was

typical of the kindness and generosity of so many people all the time I was away.

It was now early December and Drew was ready to solo. It was Sunday and we're out at dispersal where the Wimpy was parked.

Drew said, "Okay which of you guys want to ride in the rear turret while I see if I can fly this thing by myself?" Without blinking an

eye I said I'd give it a whirl and away we went. I remember heading down the main East-West runway and we were approaching the

lift off point when I sensed a rise in the runway, something like you find on some country roads. Drew held the nose down for

another few seconds to gain more speed. Then he pulled back on the control column and in a flash I knew we were airborne. Our

young pilot completed the circuit and came in for a perfect landing. In the following weeks Drew proved to be an excellent pilot and

the entire crew had every confidence in his ability. Incidentally when Enid and I returned to Pershore in 1977, we drove down the

same runway in our Ford Cortina, and felt the same rise as we scooted along. It seems that some things never change-at least not in

35 years.

From this point on we progressed quickly and after one cross-country flight with an instructor on board, we as a crew, were on our

own. We flew a series of training flights around England and Wales and completed our assignment without any serious problems. I

felt perfectly at home flying with Drew, Eric, Rex and Don and was looking forward to the days ahead.

At this point Drew got word that he had been awarded a commission. Our crew was granted a 48 hour leave for Drew to go to

London to order his officer's uniform and other things he would need. The English guys went to their homes and I headed for

London with Drew. It was my first opportunity to visit the big city - Drew had been there a couple of times. We arrived at

Paddington station and took the underground to Leinster Gardens, a leave club for aircrew. I was straight off the farm and here I

was in one of the great cities of the world. In the pre-war years, almost no one traveled to distant countries but here I was on an all

expense trip to England.

Drew went to the renowned tailor Austin Reed in Oxford Street in the heart of London. You will note that I said in. For some reason

the English say "in" rather than "on" when referring to a street. Drew got measured for his uniform, bought a flat hat and an officers

greatcoat and trenchcoat. This partially outfitted him and his uniform would be delivered to Pershore later. We didn't have much time

to visit the historic places other than walk around Trafalgar Square and Piccadilly Circus. We went to see a first-run movie The

Road to Morocco starring Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. At the time I thought it was uproariously funny. In

later years I saw all the 'Road' movies and they weren't all that great. One thing I remember about wartime London was the long

queues outside the cinemas where the line stretched around the block. It was commonplace to wait two hours or more to get in to

see a movie. Amateur entertainers, or buskers as they were called, took advantage of this captive audience and made an absolute

fortune as they sang, juggled or played a musical instrument. The tips were generous, sometimes in the form of pound notes which

had an exchange rate of $4.80, and allowing for inflation, would be equivalent to $50.00 today.

Drew and I returned to Pershore and Drew moved to officer's quarters. We resumed training in earnest and our only breather was at

Christmas. Most of the British guys went home and the Canadians stayed on base. I found it a very lonely time although we were all

in the same boat. It was the first time that most of us had ever been away from home at Christmas. Still we were the lucky ones

when we realized that by 1942 it was already the fourth Christmas overseas for the First Division Canadian Army guys. Of collision

a lot of the soldiers had British girlfriends or wives by then. Not many of our aircrew bunch were getting themselves involved - the

future was so uncertain. One exception was my old friend Johnny Boivin on one of the courses ahead of me at Pershore. One day in

the mess, a pretty WAAF waitress was pointed out to me and someone explained that she was Johnny Boivin's fiancé. That seemed

okay to me until I learned that this young WAAF had already married two Canadians stationed at Pershore earlier. In both cases

these unfortunate young airmen had got the chop and Johnny was all set to be her third husband. Whether they married I don't

know for sure but Johnny Boivin's plane crashed a few weeks later in the Welsh hills, while based at a Bomber Conversion Unit in

Yorkshire. All the crew died.

After Christmas we continued to flying as often as weather permitted. We celebrated New Year's Eve by starting out on a night

training flight which was to terminate with some practice bombing at a range in near Pershore. One feature of night flying that

bothered me was hearing the squeakers that created a high-pitched intermittent sound, warning that your aircraft is approaching or

perhaps already inside a concentration of barrage balloons. This was a dicey situation due to the heavy cables suspended from the

balloons and so designed that they could easily bring down a low flying enemy aircraft. By the same token they could be equally

damaging to friendly Flyers. We didn't hear any squeakers this time, however the weather turned so bad we had to find our way

back to base and cancel the practice bombing. By this time it was too late to do anything very exciting to welcome in the New Year.

I didn't drink - the pubs were closed anyway by this time. One character in the neighboring hut did his bit by firing flares down the

chimney.The multicolored cartridges fired from a Very pistol produced a pyrotechnic display and 1943 really did come in with a

bang.

We completed another three cross-country flights and were gaining experience all the time. I had every confidence in Drew's ability

and my only fear was the danger of a midair crash. Much of our flying was in and out of clouds and there were so many airbases in

England that the potential for collision was very real. We were doing well as a crew and with only about two weeks left at OTU we

were briefed for a Bullseye exercise on the night of January 15, 1943. A Bullseye exercise was designed to simulate operational

conditions as closely as possible. For example we carried a full load of bombs even if they were sand filled, we flew as high as the

tired old Wimpy could manage, and we were to be intercepted by friendly night fighters and searchlights along the way.All of this

was pretty exciting and we thought we were big-time.

We took off just before 6 PM - darkness came early in January. The sky was clear with no moon and there was no snow on the

disregard. The takeoff was uneventful and we were now getting used to the slight rise in the runway that gave the sense of premature

liftoff as we hurtled across it. For the first hour the flight went smoothly as we flew a normal cross-country exercise from one

turning point to another - it was still too early in the Bullseye flight to be confronted by friendly night fighters.

There was no warning of impending trouble, no explosion, not even more vibration than usual - the Wimpies assigned to the training

units had been through the wars literlly and did some shaking to show their age. It was now about 7 PM and I was standing beside

Drew looking around for other aircraft when I noticed a flame from the starboard engine. At first I thought it was a normal condition

as part of the combustion process, but then realized that we had a fire on our hands. I pointed to the engine and Drew immediately

shut it down and feathered the prop to reduce drag. At the same time he pressed the Gravenor switch which activated a fire

extinguisher in the engine. The flames died down a little but within seconds flared up again with a vengeance and soon began to lick

away at the fabric on the wing. Drew tried every trick that he knew including diving the aircraft to hopefully extinguish the flames. All

this was to no avail and the fire in the engine and the wing area continued to spread.

At this time we were losing height rapidly and Drew gave the order to abandon aircraft. At the same time he called "May Day"

which Is the international distress call. I buckled on my chute and went down to the escape hatch in the nose. The hatch cover

came off easily and I sat on the ledge and dropped through. It is something you do without thinking about. I have no idea whether I

counted three before pulling the ripcord but I could feel the jerk and the beautiful white canopy blossomed overhead. I was floating

down about 2000 feet above terra firma. Almost immediately the aircraft plunged into a field of short distance from a small village.

I landed softly in a meadow near a hedgerow and heard a rustling on the other side. Although thinking it might be a farm animal, I

called out anyway. What a relief to hear a London accent on the other side and to recognize the voice of Don Burge our rear gunner.

Together we walked up the hill with our parachutes slung over our shoulders. As we reached the top of the hill, even in the blackout,

we could see that the village consisted of only a few houses, one or two shops and of course a pub. We went inside where there

was plenty of activity and lots of chatter. The locals in this quiet part of England were quite excited about the air crash which they

heard just moments before. I was about to call the base to report the crash, when in walked Eric and Rex accompanied by the

Home Guard. These were civilian reservists always on the lookout for downed German aircrew. We were not far from Coventry,

and although the large scale air raids by the Luftwaffe were a thing of the past, there were still scattered attacks. When our aircraft

was seen to crash, the Home Guard was taking no chances and out they rushed in case it was a Jerry kite that had gone in.

The villagers soon started plying the downed airmen with drinks. Of course I was too pure to partake of the demon rum - after all, I

had signed the pledge at Welcome Sunday School. We were all relieved to be alive and our only concern was whether Drew had

time to bail out. Our worst fears were soon realized when we learned that our pilot and good friend had in fact died in the flaming

wreck. I call the base at Pershore and spoke with the officer in charge of

operations. I will always remember the first question. "Was the aircraft damaged?" It was only later that he asked about the crew.

Perhaps it was not intentional but it seemed that the decrepit old Wellington was a higher priority than the crew inside.

We learned that the little village where we landed was Orton-on-the-Hill on the Warwickshire border. The name didn't mean anything

at the time, however on a trip to England in 1977, Enid and I were told by a villager that Handel often spent time at Orton-on-the-Hill

where he was inspired to write some of his famous compositions.

After a couple of hours, a vehicle arrived from RAF Bramcote which was a base a few miles away. It was a makeshift ambulance

into which Drew's charred body was placed. Some callous official suggested we could all ride the same vehicle but this was soon

countermanded and a lorry appeared. We four survivors piled in and headed for Bramcote which turned out to be an OTU much

like our own. The personnel were mostly Polish airmen training to bomb Germany which suited them just fine.

At Bramcote, quarters were found for us and a RAF Medical Officer came around to see us which was a nice touch. He asked how

we felt and since no one had so much as a twisted ankle, he didn't get much business. He gave us some sleeping pills and suggested

we take them. He was probably right since it was only now that we realize this business of flying can be downright dangerous. For

some strange reason it hadn't quite registered that we had narrowly escaped with their lives and had lost a close friend in the space

of a few seconds. Without knowing it we were likely in a mild state of shock.

As far as I can recall I slept fairly well and had no recollection of what we did the following morning. After lunch transport arrived

from Pershore and we headed back to base. There were tarpaulin sides on the lorry, however as we passed through Coventry we

could see the devastating results of the Luftwaffe attack some two years before. Further along we realize that we were in Stratford

and my thoughts went back to Port Hope High School and Miss Hagerman my English teacher. She did her best to make

Shakespeare interesting and here I was visiting the bard's hometown if ever so briefly

We arrived at Pershore around dusk and all of Drew's friends, especially the pilots crowded around to find out what happened to

their 19-year-old friend. It was fresh in our minds so was no problem to recount the sad details. It was then that we learned there

had been another fatal crash on the same night when a Wellington pranged on the edge of the Pershore airfield. The crew, from

another course, was practicing circuits and landings and the pilot and two others were killed. The pilot F/S W. J. A. Duplin and a

gunner Sgt. W. E crisis. Barr were RCAF and the other fatality was RAF. The dual crashes set the stage for a large military funeral a

few days later. Drew, a recently commissioned officer and the three NCOs were buried in the military section of the Pershore town

cemetery. I didn't know at the time that Norm Snelgrove, a good friend from high school was already buried there after his fighter

plane slammed into a nearby hill just three months earlier. Our crew was given four days leave and I went to London.

Upon returning we learned that our navigator Eric Antrobus had decided to pack it in - he was so shaken that he wanted out of

aircrew. This took a lot of courage on his part since refusing to fly was a serious matter and the term "lack of moral fiber" or LMF

carried demeaning overtones whenever an airmen grounded himself. I don't know what happened to Eric- he disappeared from the

station one day without saying goodbye to any of the crew.He would lose his Sergeant's stripes for sure and I presume ended up in

some ground trade. He was a nice chap and I hope he got along okay.

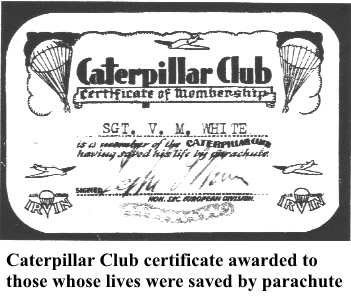

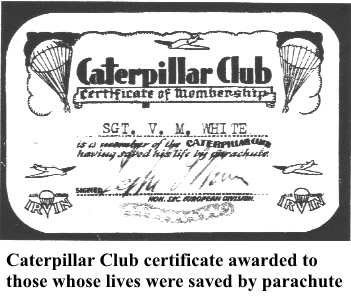

About this time I learned that early as a result of my bailout, I could apply for membership in the Caterpillar Club.

This was news to me and I visualized that there would be a building somewhere with a lounge, library, dining room, bar etc. where

members could meet. I soon found that it was not that kind club. The Caterpillar Club is on paper only and is a massive registration

of all those who have saved their lives by parachute. The organization is under the auspices of the Irving Air Chute Company. When

an application for membership is received and verified a handsome laminated wallet size card is issued by Irving in the name of the

applicant. The real prize is the gold Caterpillar pin with ruby eyes awarded to members and usually worn on the lapel. The pin is

inscribed with the members name and is a point of instant recognition all over the world. I applied for and received my Caterpillar

pin and it is still a valued possession to this very day.

When we were on leave there were more fatal crashes involving Pershore aircrews. From our own course Joe Cornfield and his

crew (five in all) were killed on a night cross-country flight. At the time it was said that they flew over a prohibited area on the east

coast of England and were shot down by one of our own night fighters. Postwar records simply show that the aircraft broke up in

the air so I'm not sure what really happened. The gunner in that crew was a guy named Snyder from Kansas. I knew him well - he

was in the bunk next to me on the Awatea on our way overseas. Ten others died when two Wellingtons collided in broad daylight

over the bombing range. They were on the course behind us. Such loss of life was tragic, and we weren't anywhere near Germany

yet.

The three of us remaining of our original crew of five, flew some cross-country flights with training instructor pilots. After a week or

so we were assigned another pilot Maxwell, an Englishman, who had joined the RCAF in Vancouver from the Merchant Marine. It

never worked out. We did four night cross-country flights and he repeatedly said that he wanted to be transferred to daylight

bombers. Apparently Max knew something the instructors hadn't picked up. His landings were terrible, however we graduated from

OTU with him as our skipper. I had serious misgivings about his competence but there was nothing I could do. We also picked up

another navigator to replace Eric Antrobus.

On February 10, 1943 our crew was posted to 427 Squadron, 6 Group, RCAF.

Top | Back | Next

To continue select Back or Next which will move you consecutively, back or forward, through the book or make a selection from the column on the right which will take you to that part of the book.