Canada's Cold War Fighter Pilots

by Colonel W. Neil Russell, CF Ret.

Part Two

1 Air Division, 1951 to 1963

While the preceding paragraphs gave an overall view of the Cold war, there is much more to relate from the Canadian perspective. In April, 1949 Canada signed onto the multinational North Atlantic Charter under which an attack against any member was considered an attack against all. Military planners concluded that Canada needed an air defence force of nine squadrons of all-weather fighters, while also assisting the defence of Central Europe by deploying twelve fighter squadrons. The Canadian commitment to Europe was designated "1 Air Division". Temporarily its headquarters was in Paris, but it later moved to Metz in North Eastern France. In addition to an Air Officer Commanding with his headquarters staff, the base at Metz included a state-of-the-art British made long range radar unit code named "Yellow Jack" a combat operations centre, a communications centre and a support unit. A logistics base was established at Langar, England, supported by a detachment of multi engine transport aircraft, Dakotas and Bristol Freighters, flown by pilots from Air Transport Command.

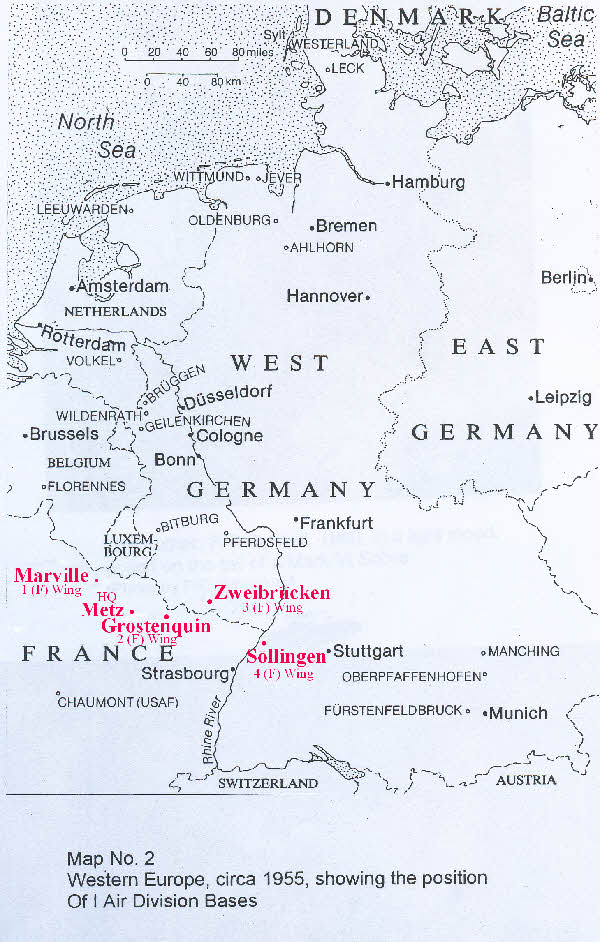

Initially, one wing of the Air Division was formed at North Luffenham, England, but by 1955 four wings were located in Western Europe as follows: No. 1 Wing, Marville, France; No. 2, Grostenquin, France; No. 3, Zweibrucken, West Germany; No. 4, Baden Soellingen , West Germany. Looking from above the four wings formed an irregular diamond, all within a day's drive of Metz.

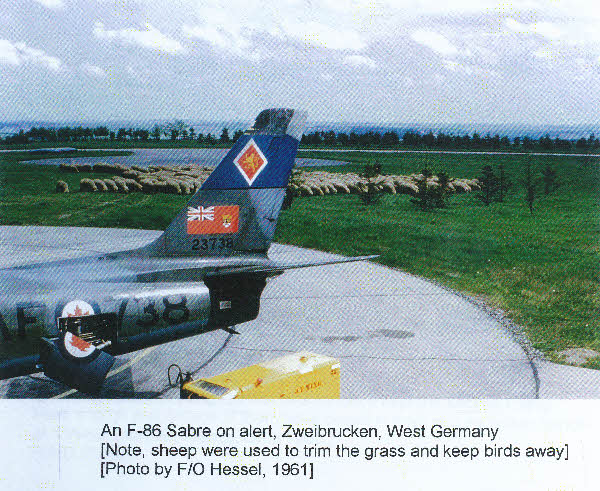

Each wing, commanded by a Group Captain [Colonel], was like a small city with a large airport. Wing Operations under a Wing Commander [Lt Colonel] was responsible for the airfield, including an air traffic control tower and ground control approach radar which could recover aircraft when cloud ceilings were as low as 200 feet. The "city" included housing for single and married personnel, food services in officer, NCO and airmen's messes, a hospital, schools for dependent children, civil engineering, supply, ground transport, ground communications, and the most vital element, a large aircraft maintenance unit responsible to keep the air squadrons supplied with serviceable aircraft. The operational forces at each wing consisted of three fighter squadrons, each originally equipped with 25 Canadian-built F-86 Sabre aircraft. 1 Air Division's total of 12 squadrons with 300 aircraft [plus spares] constituted "...the largest RCAF fighter force ever assembled". [Quote and details above from Canada's Air Forces, 1914-1999, by B. Greenhous and H. Halliday, air force historians]

This mention of the Canadian F-86 Sabre aircraft introduces a good time to describe the Canadian production of this highly successful aircraft. Designed by the [American] North American Aircraft Corporation, the F-86 first flew in 1947 and, in the hands of pilots the United States Air Force, plus 22 selected Canadians, achieved success against Russian-designed MIG-15s in Korea. With Canada’s need for a fighter for home defence as well as in Europe, the Government encouraged an agreement between the North American Corporation and Canadair Limited, Montreal, to manufacture improved versions of the F-86 in Canada. The prototype Canadair Sabre Mark I and production Mark IIs used the original American engine, but had better, power-assisted controls. Between 1952 and 1953, 350 Mark IIs were produced, most for the RCAF, but 60 for the USAF for use in Korea. There was only one Mark III, used as an engine test bed and for publicity, Jacqueline Cochrane's Woman’s Speed Record. The Sabre Mark IV, of which 438 were produced in Montreal, was outwardly similar to the Mark II, but transferred directly to the British Royal Air Force for use in NATO. By July, 1953 the first Canadian jet engine was ready, the Avro Canada Orenda 10, rated at 6,500 pounds of thrust. These improved engines, plus a larger solid leading edge wing, gave the next generation Sabre, the Mark V, improved rate of climb and ceiling. Canadair produced 370 Mark Vs, most for the RCAF to replace Mark IIs, with 75 transferred to the newly emerging West German Luftwaffe.

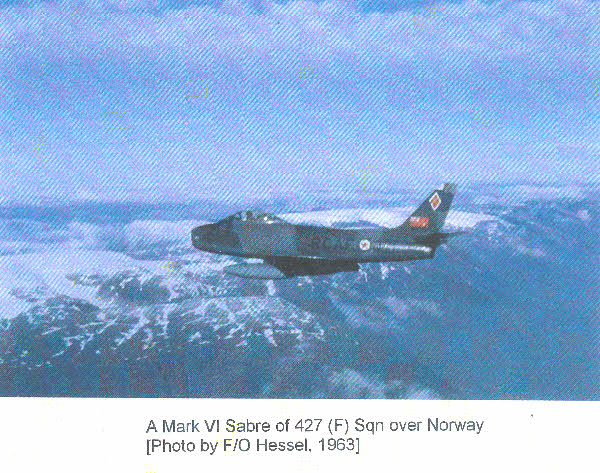

The ultimate version of the Canadian F-86 was the Mark VI. This carried the two stage Orenda 14 engine rated at 7,275 pounds of thrust and reintroduced leading edge slats which had been developed for earlier versions of the Sabre. The increased thrust gave the Canadian fighter more speed and a higher ceiling [54,000 feet], while the leading edge slats allowed a tighter manoeuvring radius. The Mark VI, like its predecessors, was armed with six .50 calibre machine guns, controlled by a radar ranging gun sight. As again quoted from Greenhous and Halliday, "In its day the Mark VI, was known as the best "dog-fighter" in NATO and probably, in the World". It certainly was highly respected by pilots of other NATO air forces and in the event of war would have measured well against aircraft flown by the Warsaw Pact. Canadair produced a total of 655 Mark VI Sabres; 390 of these went to the RCAF for use in the Air Division; others ended up in a total of ten friendly air forces, as well as Canada’s celebrated aerobatic team, the Golden Hawks. In all, a total of 1815 F-86 Sabre aircraft were built in Canada. These, along with the advanced Orenda engines, contributed to the building of Canada's significant aerospace industry.

Returning to 1 Air Division, I will now describe a typical squadron… 427 (F) [Lion] Squadron which I joined in January, 1959. The Squadron was based at Zweibrücken, in the Saar region of West Germany, three kilometres from the French Border.

In NATO terminology, 427 was designated "Interceptor Day Fighter", meaning that it was expected to operate mainly in daylight. The squadron's war mission was to help protect Central Europe from air attack by the Soviet Bloc. Squadron personnel included an Officer Commanding [OC] with the rank of Squadron Leader [Major], two Fight Commanders, nominally with the rank of Flight Lieutenant [Captain], a maintenance officer, an admin clerk and 30 line pilots, mainly Flying Officers [Lieutenants]. Aircraft maintenance was provided by Wing Central Maintenance with a detachment of technicians assigned to the Squadron for daily servicing. Normally the Squadron operated from home base; however, it was to be prepared to deploy on short notice.

Every nine months there was also a pre-planned deployment…to Sardinia, for the use of the NATO air-to-air gunnery range. Squadron pilots practiced their war mission through daily exercises during which Yellow Jack, the long range radar at Metz, vectored them to intercept "aggressors" from another wing. Periodically there were larger exercises sponsored by the Air Division's higher authority, 4th Allied Tactical Air Force, and, a few times per year, NATO wide exercises, simulating a large scale attack from the East. For these rehearsals of the war role, the whole Wing would go to high readiness, including the activation of semi hardened bunkers to protect key personnel in the event of nuclear and/or biological attack. If no formal exercises were scheduled, the Squadron could organize its own training. In this case a flight of four aircraft would take off, climb through the haze and cloud until "on top" and look for targets of opportunity. These sorties occasionally resulted in as many as 32 fighters, American, French, Belgian, Dutch and eventually German, swirling on high in a grand aerial circus. In peacetime, of course, guns were not armed. The objective of each pilot was, while avoiding getting an "enemy" on his own tail, to get behind a target aircraft, close to 1500 feet or less and capture the "enemy" on the film of a cine camera which recorded images through the gun sight. On return to base, each flight would "debrief" and a fighter weapons instructor would assess each pilot's film after which he could, or could not, claim a "kill".

Beginning in 1956, one squadron of each 1 Air Division wing was replaced by a squadron of CF-100 all-weather fighters; however, for simplicity and continuity, the text which follows will continue to concentrate on the Sabre aircraft and their pilots.