Canada's Cold War Fighter Pilots

by Colonel W. Neil Russell, CF Ret.

Part Three

The Sabre Pilots of 1 Air Division

The previous two parts described the Cold War and the origin of 1 Air Division, its role and organization, now its time to talk about the Sabre pilots of 1 Air Division. A typical pilot would be a Flying Officer [Lieutenant], 21 or 22 years old. He had to be at least a high school graduate and accept a five year short service commission as an officer in the RCAF. After background security checks, comprehensive medical examinations and a battery of aptitude tests, if accepted, he would be sent to initial pilot training on the Harvards at Centralia, Ontario or one of three bases in Western Canada. (later the DeHaviland "Chipmunk" became the initial trainer then continuing on Harvards) If still successful he would go on to advanced training on the T-33 Silver Star at one of three bases in Manitoba, graduating with the coveted RCAF pilot's wings. If still successful and recommended, approximately a year after entry, he would enter the most exciting part of his training, the Sabre Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Chatham, New Brunswick.

Few pilots can forget their first flight on the Mark V Sabre at the OTU. There was no two seat version of the Canadian F-86; your first flight was "for real." Granted, there was a simulator of sorts. It replicated the cockpit instruments and controls, and experienced F-86 pilots could lead you through engine starting, taxi and some basic emergency procedures; but on the day of your first flight, an instructor would stand on the wing of your aircraft, watch you get the engine started, then pat you on the shoulder saying, "Its all yours; good luck." Although first landings were a little bouncy, most of my group of students had no trouble; however, one classmate got a case of the nerves, had to be talked down by an instructor in the control tower and decided that single seat jet flying was not for him.

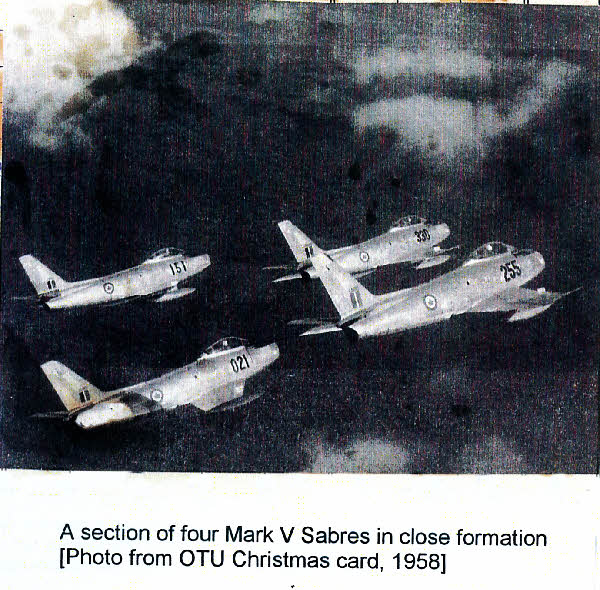

After three solo fights at the OTU, my group immediately started close formation flying. Flying in close formation is basic for all fighter pilots. It's not just for "show" but for "efficiency", to allow four aircraft to take off, join up, and climb through cloud making one radar "blip". Once above cloud, Canadian fighter pilots used a loose, "finger four" battle formation. The flight [section] leader was the primary hunter/shooter; Number Two was a wing man, guarding his tail. Number Three [element leader] was also a hunter/shooter, flying abreast or behind the section leader, with Number Four guarding his tail. Returning from the "hunt" and "battle", the four aircraft would re-assume close formation, descending to base as if they were again one radar blip. While practicing both close and battle formation on every trip, student pilots at the OTU soon went into air-to-air fighting, first one-on-one, then two-on-two, and four-on-four. It was exciting for young pilots, and not without risk.

After acquiring some 50 hours on the Mark V Sabre, OTU student pilots joined the real fun, firing the guns, first, against stationary targets on the ground, then air-to-air. In the latter, four aircraft lead by an instructor would take off, fly to an air-to-air gunnery range located off the coast and space themselves in line-a-stern, above and abeam a 15 metre long drogue ["flag"] towed behind a target aircraft. Taking turns, each pilot would dive his aircraft in a curve of pursuit toward the flag, watch while his range-finding radar acquired the target, and close in to 1,200 to 800 feet, smoothly tracking the target, firing for a few seconds, slipping past the flag and returning back up to the "perch". Each of the four firing aircraft was armed with .50 calibre bullets tipped with a different coloured wax. When the flag was towed back to base, retrieved and inspected, the great hope was to find holes made by your colour of bullets. An eventual passing grade was to have a score of 15 or 20%; a few instructor "aces" could achieve more than 50%. I was never an "ace" in air-to-air gunnery at the OTU, but I passed the course and before long, in January, 1959, I was on my way to my first operational posting as a fighter pilot of 1 Air Division.

Friends have asked me if I had any particularly interesting flights while on Sabres overseas. Yes, especially one where I saw the real "enemy" and I armed my guns. The occasion was the first time I was a member of the special standby flight, with six guns fully loaded, called by NATO "Zulu Alert". My log book showed 500 total hours of which just 130 hours were on Sabres. We were "King Formation", King Lead being F/L Mart Eisner, an experienced WWII pilot upgrading to section lead; his wing man, King Two, was F/O Eddie McKeogh, Squadron Fighter Weapons Instructor. King Three was our highly experienced OC, S/L Hal Knight. I was "Tail End Charlie", King Four. We had inspected our aircraft, set parachutes and helmets in the cockpits ready in case of the need of a quick start, and had just returned to the readiness hanger expecting a quiet morning of knock rummy, when we received the command, "King Formation, take off on a live scramble; head 090 degrees [East]; make angels four zero zero [40,000 feet]". The OC was sure it must be a mistake, stating, "The Air Division always uses practice scrambles; never a live one [Real emergency]." But half an hour later, still flying east, and having been handed off from Yellow Jack to an allied radar, "Race Card", we were informed that there was an unusual amount of air activity across the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia. Our job was to mount a show of force on our side of the border. No sooner had this been explained when King Two, Eagle Eye Eddie McKeogh, transmitted, "King Lead, Bandits, 12 o’clock, 30 miles, level". From behind, squinting my eyes, I couldn't see any "bandits", but I didn't have long to look before our formation leader transmitted, "King Formation, arm your guns". "Arm our guns?!?", I questioned, "Does Lead remember that with just a slight squeeze of the trigger we could spray bullets all over Germany"? But, that's what the leader had ordered, so quickly I went through the three steps ending with the arm guns switch. There was a bumping vibration and sound, ker-chunk, ker-chunk, as six armour piercing rounds thrust forward into the breach blocks of the six machine guns in the nose of my Sabre.

I remember my heart was beating fast as I tried to fly as smoothly as possible, my head and eyes on a swivel, when Race Card finally gave us the order to turn left to 350 degree [North], parallel to the border. Then, as we turned, I saw them. at least three, possibly more, silver, swept wing aircraft, probable MIG-17s, flying parallel to us, approximately 15 miles distant. Being low on fuel, we didn't have long to impress the Czechs with our little show of force. Released by Race Card, our throttles back to idle, we glided into Erding, a NATO air base near Munich, waking up the sleepy air traffic controller with the announcement that we were, "four Canadian Mark Six's, landing with hot guns". The significance of the hot guns was that, once the Canadian F-86's machine guns were armed, it was not safe to shut off electrical power until the guns had been de-armed. Fortunately, no member of King Formation had itchy fingers and Eddie McKeogh was able to go from aircraft to aircraft, pulling each belt of .50 calibre shells out of the breach blocks so we could safely shut off battery power.

Later, after taking off from Erding and uneventfully reaching home base, we debriefed. S/L Knight complimented Eagle Eye Eddie as the first to see the bandits; he also agreed with King Lead, Mart Eisner, with his order to arm our guns. As the OC said, "For every bandit you see, there can be more; we could have been bounced at any time". And to me, squadron rookie, he thought I had flown a good battle formation position, "...except, perhaps, just a little too close toward the end." I explained, "Thank you boss; I was doing my best to look out and guard your tail; however, once I had seen the enemy, there was no way I was going to lose you."

Any other incidents? Yes, a short, but significant, one. On one of those flying circuses north of Zweibrücken, with perhaps 16 aircraft swirling high in the sky, I had got behind an "enemy" aircraft and was concentrating on tracking him through my gun sight, when my aircraft shook and a shadow passed over me. Back at base, when another pilot and I were reviewing my gun sight cine film, we saw the cause of the bump and shadow. A French Mystere IV had passed from above to below, its profile nearly filling the windscreen, perhaps less than 50 feet in front of the nose of my aircraft. I'm very lucky to be alive!

Many other Canadian Sabre pilots were not so lucky. RMC classmate, Bob Hallworth, and OTU course mate, Jack Faulds, were killed in mid air collisions. RMC classmate, Eddie Gagosz, wrote himself off by crashing his Porsche into a tree. In all, between the years 1951 to 1963, 107 Sabre pilots were killed in accidents in Canada and overseas. Most were buried with military honours in the RCAF Cemetery, Choloy, which in grim sense of humour the Sabre pilots used to call "Five Wing". A memorial to the 107 stands on the grounds of the RCAF Memorial Museum at Trenton, Ontario.

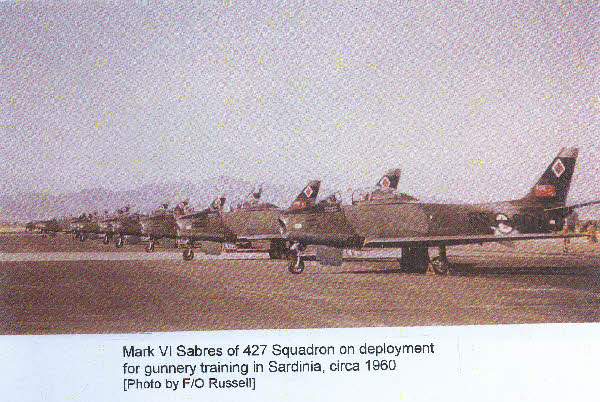

There are many other stories which could be told, some of them humorous. Deployment for air-to-air gunnery in Sardinia was always a high time for squadron pilots.

At first we slept in bunk beds, as many as 30 men in a large barrack room dating back to the Second World War. Late one night Norm Guizzo and Hank Gritter, coming home from the mess, invited a donkey into the barracks. The only trouble, the poor creature backed into a hot space heater. What a stink! Another incident, not so funny at the time, a tow plane while above cloud, got too close to the coast. Four sabres scattered .50 calibre bullets onto a tourist beach. No one was hurt; there was no damage; the mistake might have gone unnoticed, except, oh,oh, on holiday, near the beach, was none other than Air Marshal Sir Harry Broadhurst, Commander 2 ATAF. As I recall, no one was punished; however, a rule was soon published that the pilots of aircraft towing drogue targets must at all times be able to see the coastline and be 100% sure they were flying in the published air-to-air range over the sea.

These incidents, while perhaps not completely typical, represent the type of flying which was done by 1 Air Division's Cold War fighter pilots. The young short service commission officers worked hard, played hard [they drank a lot, particularly when letting off steam at Friday Beer Call]; but they flew well and many were good leaders. While a squadron had an OC and two flight commanders, the informal leaders were the young most experienced pilots who had qualified to be four plane formation leaders. The best formation leaders were renowned all over the Air Division. And if one had been chosen to go back to the OTU to train as a "Fighter Weapons Instructor", he was "god". As stated by Greenhous and Halliday: "Canadian Sabre pilots regularly bounced and outflew their rivals in other air forces. On three occasions RCAF Sabre teams won the Guynemer Trophy, emblematic of gunnery supremacy in NATO air forces. The Sabre years were the happiest times for those serving in 1 Air Division; in retrospect, many would consider it the RCAF's golden age".