Part 1 - Canada

- Manning Depot, Quebec

- #4 Repair Depot, Scoudouc, N.B.

- #3 Initial Training School (I.T.S.)Victoriaville, Quebec

- Ancienne Lorette, Quebec

- #9 B&G Mont Joli, Quebec

- #1 Central Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba

- "Y" Depot, Halifax, N.S.

- Royal Air Force Ferry Command, Dorval, Quebec

- RAF Repat Depot, Moncton,N.B.

Part II - Britain

-

Part III - Prisoner of War

Part IV - Home Stretch

Postscript

The scenery from Halifax to Montréal hadn't changed much in the intervening years but it looked mighty good to us. The people in the fields waved at the passing train and in the station where we stopped the friendly Maritimes were there to greet us. There was sadness too. I remember our stop in St. John, New Brunswick where one gentleman on the station platform was moving from one group of POWs to another asking if any of us knew anything about his son (he gave us a name) who was missing on air operations. It was a last hope on the part of a bereaved father and regrettably none of us could help. In Moncton by pure chance I met Mrs. Austen and her daughter. They were at the station to meet a relative arriving on another train. The Austen family were kind and hospitable to me when I was stationed at Scoudouc in 1941 and again before I went overseas. It was just another nice thing that kept happening to me.

We arrived in Montréal in mid afternoon the following day and found ourselves on a railway siding outside the RCAF Station at Lachine. I recognized the place immediately having lived there in the summer of 1942 while I was with RAF Ferry Command waiting to navigate an aircraft to Britain (it didn't happen!). We were ushered into a huge drill hall and there were hundreds of people waiting to greet the arrivals. There were friends and relatives bursting out of the crowd from all directions. They were mostly Montréal family members on hand but I remember so well, Jimmy Russell being swept off his feet by his wife Mary and Betty Floody being there to meet Wally. These gals had travelled from Toronto to be with their husbands ASAP.

I didn't expect to be met by anyone but I heard my name called and lo and behold there was Jean Maquire, a girl I had met at Air Force House a few times in 1942. She heard a radio announcement that Air Force POWs were arriving and decided to drive to Lachine on speculation. Jean invited me to her home in Westmount and her mother and dad insisted I stay for supper (or dinner). As a favour Mr. Maguire drove me to the Snowden area to meet the parents of Max Shvemar my navigator died during or after bailing out. Mrs. Shvemar, a Jewish lady, was overjoyed to see me but quite emotional. I told her everything I knew but could give her no explanation why Max did not survive. They thanked me for coming to see them so soon after arriving back in Canada. The Maquires drove me back to Lachine.

Next day at Lachine there were administrative matters to discuss relating to our future in the RCAF. It appeared we would be released from the service since there was an oversupply of trained aircrew in Europe to staff the eight heavy Bomber Squadrons being readied for Japan. One must remember that in all our exuberance there was still a war to be won in the Pacific. We were told we would be granted six weeks leave and then proceed to the nearest Release Centre which in my case was Toronto.

I phoned the Beckett family in Valois and spent the afternoon and evening with them at their Queen's Road home. I had been a guest in their home in July 1942 when son Bob (or Robbie as he was known to the family), was on embarkation leave and it was a reminder of happier times. Bob was the eldest of four children and like myself 20 years of age (in 1942) there was a sister Joan (18) and sons Peter (9) and Michael (3). The family members were all on hand when I arrived and greeted me warmly. They asked a lot of questions about my experience overseas and were generally grateful that I came through okay, whereas their son was killed on his first bombing operation as an aircraft Captain. I'm glad I was able to tell them of several weeks that Bob and I were stationed at the same Operational Training Unit in England before he went to the squadron. They seemed to appreciate hearing from me that he would read aloud portions of his letters from home and invariably carried a wad of family pictures in his wallet. I reminded them of the fact they already knew that Bob (or Robbie) was a super young man, well liked by everyone and someone who was always smiling. They thanked me time and again for the visitation and wished me well and a good life. We kept in touch with the Beckett family for many years including the times we lived Pointe Claire. By coincidence Hank Canning, a former resident of Valois, is now living at Ennisclare (ed. note &dash:Oakville/Bronte Condominium) and recalls his high school days when he and Bob Beckett played in the same jazz group. It really is a small world.

July 17, 1945 dawned bright and clear and this was the day we were Port Hope bound. We packed our belongings and proceeded to the drill hall one last time. We had to line up for travel vouchers and to our surprise were handed five crisp $50.00 bills for spending money while on leave. It came out of our eventual settlement but was a nice touch and a real benefit to those who had not yet established bank accounts. In those days credit cards were almost unheard of. And so with this loot we were all sent to board the afternoon train bound for Toronto. It was a happy time but tinged with sadness too as we said goodbye to our kriegie pals who were scattering to all parts of Canada. Even in the era of modern travel there would be some we would never see again. However there have been wonderful ex-POW reunions in Vanouver, Calgary, Ottawa(2), Toronto (5), Southhampton and London which Enid and I attended. And so we have a storehouse of happy memories.

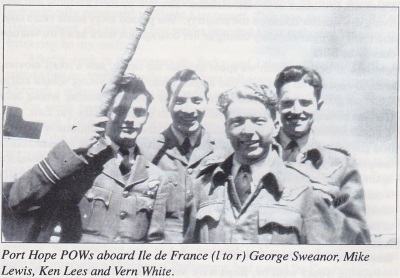

Getting back to the Toronto train, our kriegie passenger list represented many of the towns and cities in southern Ontario. We made all the regular stops along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario and there was a fair crowd at places such as Cornwall, Bockville, Kingston and Belleville to meet their hometown kriegies. At Port Hope we expected our families and perhaps a few friends would be there. How wrong we were. As we rattled across the viaduct, Mike Lewis looked up the tracks and could hardly believe his eyes. "It looks as if the whole town is out there," he said excitedly. As we pulled into the station we could see for ourselves‐there were people everywhere hundreds of them. A big attraction was Mike Lewis who left Port Hope in 1938 to join the Royal Air Force and had been a POW almost 4 years. Then there was George Sweanor, Ken Lees, Alan Thompson of Cold Springs and yours truly. (Art Woods arrived next day). The huge turnout was typical of the tremendous loyalty and support given to the Armed Forces by the citizens of Port Hope and surrounding area.

add photo

Getting back to the Toronto train, our kriegie passenger list represented many of the towns and cities in southern Ontario. We made all the regular stops along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario and there was a fair crowd at places such as Cornwall, Bockville, Kingston and Belleville to meet their hometown kriegies. At Port Hope we expected our families and perhaps a few friends would be there. How wrong we were. As we rattled across the viaduct, Mike Lewis looked up the tracks and could hardly believe his eyes. "It looks as if the whole town is out there," he said excitedly. As we pulled into the station we could see for ourselves‐there were people everywhere hundreds of them. A big attraction was Mike Lewis who left Port Hope in 1938 to join the Royal Air Force and had been a POW almost 4 years. Then there was George Sweanor, Ken Lees, Alan Thompson of Cold Springs and yours truly. (Art Woods arrived next day). The huge turnout was typical of the tremendous loyalty and support given to the Armed Forces by the citizens of Port Hope and surrounding area.

add photo

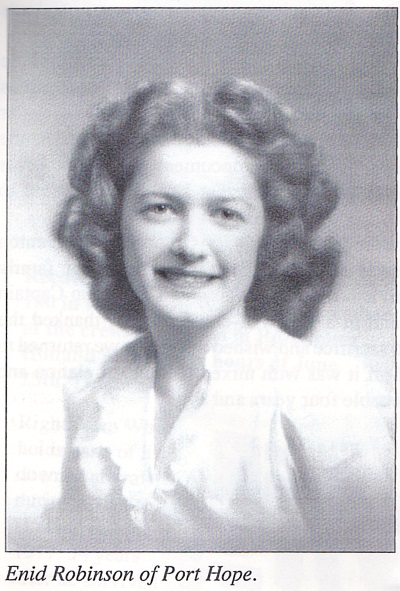

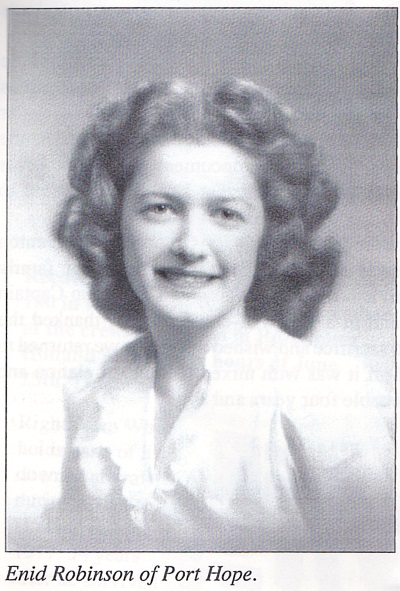

As I came down the steps to the platform I spotted my dad and thought how much he had aged in the three years I had been overseas. He looked more than his 56 years although I must have realized he had been severely wounded in France in 1918 and had worked hard on the farm while partially disabled. Mother was there too and how wonderful it was to see her. Long separations and the perils of war were especially hard on the mothers and mine was no exception. Just then my brother Allan came panting up the platform. He had been down in Viaduct Park watching a ball game when he saw the train arriving and missed my grand entrance by a minute or so. Mike and George and the others were meeting loved ones in the huge throng. The Sweanor family had shrewdly spaced themselves at intervals along the platform not knowing from which car their favourite kriegie would emerge. In my case Uncle Bill and Aunt Bertha Austen were there too and Aunt Bert and Uncle Cecil White. I was glad to report that I saw their son Lorne in Bournemouth two weeks previously and he too was itching to get home. There were dozens of other town and country people that I recognized and I did my best to shake their hand or at least wave. All in all it was an incredible welcome and spontaneous apparently. It seemed that people just wanted to be there.One notable absentee was a young lady named Enid Robison who more than made up for it later on.

Mother had planned a late supper and a small family reunion at the farm. We drove home in the 1935 Chev and the countryside was beautiful on this mid July evening. I well remember turning into the driveway and the row of maple trees looked as lovely as ever. Tip, the unpredictable collie recognized the car but I doubt if he knew who the stranger was. He didn't snarl so that was something to be thankful for. By the next day he accepted me more or less as a family member in good standing. Uncle Bill and Aunt Bertha and Uncle Cecil and Aunt Bert arrived and mother had a great array of scrumptious food laid out and we sat around the large kitchen table. There was so much to talk about since there had been no exchange of letters during my last eight months in Germany. Uncle Bill wanted to know how I got shot down and I remember saying, "Okay, I'll tell the story once and for all and that will be it." And that is precisely the way it went. We stayed up rather late and I suggested it was perhaps time to call it a night. I hadn't forgotten that farmers need to rise early. I thanked all my relatives and especially my mother for their many kindnesses during my four years away from home. It was great to be on my own turf in my own bed.

Next morning Allan drove me to Port Hope to pick up my trunk at the station. I also needed to buy some light summer clothes. That same evening Alan and I went to a dance at the Pavilion (long since disappeared) in Coburg. At the wicket I asked for two admission tickets which were all of one dollar each. I reached into my wallet for what I thought was a two dollar bill and mistakenly drew out one of the fifties, roughly the same colour. The ticket collector asked if I had something smaller and it was only then that I realized my mistake. There were others in the lineup witnessing the whole thing. was in uniform and it surely looked as if this RCAF guy was trying to be a big shot. Fifty bucks was a lot of money in those days.

In the next few days I stayed around home most of the time and may even have helped out on the farm. On Saturday evenings there was a dance at the Port Hope arena. It was a good way to meet girls and almost as important it was a gathering place for the local veterans who were beginning to arrive home in droves. It was pon one of these occasions that I met a pretty young girl who had grown up while I was away. And I liked what I saw ‐her name was Enid Robinson.

On my first trip to Trenton I went to see Mrs. Joseph Somers, mother of my pilot Lou Somers who was officially listed as missing, presumed dead. The Somers family, like the Shvemar family in Montréal, were Jewish and as I found out, Mrs. Summers had very poor eyesight. This did not prevent her from showing me a photo album filled with pictures of her son who was a football star at the University of Toronto 1937 ‐40. He was also a star hockey player and a Honours graduate in Commerce and Finance. I told Mrs. Summers how proud and fortunate I was to become a member of her son's crew after my own crew had more or less disintegrated. Mrs. Summers thanked me warmly for the personal visit and wanted to be sure I would meet her son Jerry who joined the RCAF the same week that his brother was reported missing. As a postscript I did meet Jerry Somers later in the year at the University of Toronto and followed his career with interest. Like his brother, Jerry was a brilliant student and became a full professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

A second postscript - our Halifax aircraft was discovered in August 1967 totally buried on the island of Rozenburg. The remains of Lou Somers and F/Sgt. Walton were found and buried with full military honours in the Canadian War Cemetery at Groesbeek in Holland. Jerry Somers was later quoted as saying that for his mother, by then a very old lady, it was a form of closure and put her mind to rest. Enid and I have since visited Groesbeek in 1977 and again in 1995 and witnessed the Dutch school children decorating the graves. On those same trips we also visited the graves of Max Shvemar and Jock Arthur in Rotterdam. the fifth fatality in our crew, Fred Ashby remains among the missing and his name is inscribed on the Runnymeade Memorial.

Early in August I went to the USA to visit friends and relatives. It was the only time in my life that I took the car ferry from Coburg and it was a lot easier than traveling by road around Lake Ontario. I was met at the docks by Arthur and Jean Pomeroy and daughter Fay. Art was raised on the Cranberry Road(now Victoria Street) on the edge of Port Hope and he and my dad were boyhood friends. When the war came along they joined up together in the 136th Battalion and had consecutive regimental numbers. After the war Art Pomeroy moved to Rochester where he was employed by Kodak. The Pomeroys had relatives in Port Hope and Kingston and came to Ontario every summer. Art and Jean always came out to the farm to see my folks. Fay wrote to me in POW camp nd sent pictures which were a sensation – they were in colour which was still in the experimental stage.

It was during my Rochester visit that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima with devastating results. The commentators were soon predicting an early end to the war in the Pacific. Until now it was felt that a massive land invasion of Japan would be necessary and victory at least a year away. The Pomeroy's were glued to the radio with each news broadcast‐their only son Fred was a bombardedier a on B‐29s in the Pacific. I enjoyed my few days with the Pomeroys‐they treated me like family. Upon leaving I expressed the hope that the Pacific war would soon be over and that Fred would be returned to them unarmed.

From Rochester I made a side trip to visit the Slayton who family farmed at Cohocton, near Bath, New York. Neva Slayton was my dad's first cousin and was married to Ernest Slayton. They had a daughter Eloise and three young sons. Neva and Eloise visited the Baulch family on the Lakeshore Road in Port Hope in 1942 and I met them just before I went overseas. The Slaytons showed me a good time and made sure I met the rest of dad's relatives who lived in that part of the country. While at Cohocton, the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki and almost immediately Japan's threw in the towel. The date of surrender was August 15, 1945 which is generally recognized as V‐J Day. The Americans were overjoyed since this meant the end of hostilities in the Pacific where there had been so many vicious battles and horrendous casualties since Pearl Harbor.

I returned to Canada by train via Buffalo on August 17 and stayed over in Toronto. This was planned since the next day I was an invited guest at Bob Frost's wedding in Runnymede United Church. I had been at OTU and on 427 sSquadron with Bob Frost and in the same POW camps. Frostie was a navigator in the Higgins crew the night I got the blast of flak in my parachute equipment. About a half dozen kriegies were also invited including Bob's brother-in-law Bill Howell who was best man. The picturesque Old Mill was the locale for the reception and a good bash it was. I had two weeks remaining in my leave and now that the war was over in all theatres I begin to wonder what I would do in the way of career. I inquired about Ontario Agricultural College at Guelph and found that the courses were already fully booked. Through Parky I learned that the Bank of Commerce were hiring at the princely sum of $25.00 per week. This didn't grab me since I was being paid $8.50 per day as a Flight Lieutenant. I should have known that without any skills I would never match that level conversation in civvie street. For a while I knew I could help out on the farm until I got my bearings.

On returning from the States I went to the regular dance at the local arena and hoped Enid Ruth Robison would be there. I was not disappointed and that was a beginning of a loving relationship that is still going strong. To this day Enid claims we had an earlier date arranged and I stood her up by going to the States. As a result she went out with my brother. I have no recollection of any such arrangement and can only claim insanity. To the best of my knowledge the only girl I ever stood up was in Harrogate when a German night fighter pilot interfered with my plans and I was cooling my heels in an Amsterdam prison when I was expected by a Land Army galin Harrogate I rest my case.

On returning from the States I went to the regular dance at the local arena and hoped Enid Ruth Robison would be there. I was not disappointed and that was a beginning of a loving relationship that is still going strong. To this day Enid claims we had an earlier date arranged and I stood her up by going to the States. As a result she went out with my brother. I have no recollection of any such arrangement and can only claim insanity. To the best of my knowledge the only girl I ever stood up was in Harrogate when a German night fighter pilot interfered with my plans and I was cooling my heels in an Amsterdam prison when I was expected by a Land Army galin Harrogate I rest my case.

I was due in Toronto the following week and my destination was the CNE grounds which had been taken over by the RCAF at the start of the war. It had been No. 1 Manning Depot where tens of thousands of rookie airmen were processed, indoctrinated, inoculated, clothed, drilled and fed. Now the same facility was being used as a Release Centre. When I arrived the place was a hive of activity but well organized. I had another medical and was pronounced okay except that my tonsils were enlarged. The bean counters took one more shot at explaining the debits and credits on my pay records. There were even vocational guidance and employment representatives on hand. One I remember told me about the career opportunity at the Toronto Transportation Commission with a starting wage of $0.75 per hour as a motorman or conductor trainee. In your wildest dream can you imagine me driving a streetcar? We also received information about the package of benefit plans available e.g. University or Trades training, housing under the Veterans Land Act, Gratuities and so on. In my opinion Canadian veterans were extremely well treated by our government in contrast to the meagre handouts after World War 1.

On September 4, 1945 I received my discharge certificate showing name, rank and serial number. Also shown were a list of medals and decorations which for some unexplained reason included the Africa Star. I was never near the place and of course did not make application when I ordered the other five metals from Ottawa. The official document stated that I was transferred to Class 'E' Reserve which meant that I could be recalled to Active Duty if need be.

We had our last Parade in the Coliseum with Group Captain Denton Massey taking the salute. He was a member of the farm implement family and a close relative of Vincent and Raymond Massey. The Group Captain was a great public speaker and in a few well chosen words thanked the assembly for their service and sacrifice and wished us well as we returned to civilian life. As we marched off it was with mixed feelings of elation and regret. It had been an unforgettable four years and a bit.

Top | Back | Next

To continue select Back or Next which will move you consecutively, back or forward, through the book or make a selection from the column on the right which will take you to that part of the book.

Getting back to the Toronto train, our kriegie passenger list represented many of the towns and cities in southern Ontario. We made all the regular stops along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario and there was a fair crowd at places such as Cornwall, Bockville, Kingston and Belleville to meet their hometown kriegies. At Port Hope we expected our families and perhaps a few friends would be there. How wrong we were. As we rattled across the viaduct, Mike Lewis looked up the tracks and could hardly believe his eyes. "It looks as if the whole town is out there," he said excitedly. As we pulled into the station we could see for ourselves‐there were people everywhere hundreds of them. A big attraction was Mike Lewis who left Port Hope in 1938 to join the Royal Air Force and had been a POW almost 4 years. Then there was George Sweanor, Ken Lees, Alan Thompson of Cold Springs and yours truly. (Art Woods arrived next day). The huge turnout was typical of the tremendous loyalty and support given to the Armed Forces by the citizens of Port Hope and surrounding area.

add photo

Getting back to the Toronto train, our kriegie passenger list represented many of the towns and cities in southern Ontario. We made all the regular stops along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario and there was a fair crowd at places such as Cornwall, Bockville, Kingston and Belleville to meet their hometown kriegies. At Port Hope we expected our families and perhaps a few friends would be there. How wrong we were. As we rattled across the viaduct, Mike Lewis looked up the tracks and could hardly believe his eyes. "It looks as if the whole town is out there," he said excitedly. As we pulled into the station we could see for ourselves‐there were people everywhere hundreds of them. A big attraction was Mike Lewis who left Port Hope in 1938 to join the Royal Air Force and had been a POW almost 4 years. Then there was George Sweanor, Ken Lees, Alan Thompson of Cold Springs and yours truly. (Art Woods arrived next day). The huge turnout was typical of the tremendous loyalty and support given to the Armed Forces by the citizens of Port Hope and surrounding area.

add photo

On returning from the States I went to the regular dance at the local arena and hoped Enid Ruth Robison would be there. I was not disappointed and that was a beginning of a loving relationship that is still going strong. To this day Enid claims we had an earlier date arranged and I stood her up by going to the States. As a result she went out with my brother. I have no recollection of any such arrangement and can only claim insanity. To the best of my knowledge the only girl I ever stood up was in Harrogate when a German night fighter pilot interfered with my plans and I was cooling my heels in an Amsterdam prison when I was expected by a Land Army galin Harrogate I rest my case.

On returning from the States I went to the regular dance at the local arena and hoped Enid Ruth Robison would be there. I was not disappointed and that was a beginning of a loving relationship that is still going strong. To this day Enid claims we had an earlier date arranged and I stood her up by going to the States. As a result she went out with my brother. I have no recollection of any such arrangement and can only claim insanity. To the best of my knowledge the only girl I ever stood up was in Harrogate when a German night fighter pilot interfered with my plans and I was cooling my heels in an Amsterdam prison when I was expected by a Land Army galin Harrogate I rest my case.